Inu-ô – Inu-oh - 犬王

Inu-ô – Inu-oh - 犬王

Director: Masaaki Yuasa

Country: Japan, China

Year 2021

Click Here for Italian Version

"Listen, without a name, find you it will be very difficult for me."

The chronicle of Japan is overflowing with conflicts, wars, massacres, disputes with power, legendary warriors like the samurai, ambitious feudal lords, and warmongers. One of the bloodiest and, at the same time, most legendary challenges in Japan took place in the twelfth century. The Taira clans - called Heike - and that of the Minamoto - called the Genji - were engaged in a ruthless and sadistic confrontation. The final battle was a naval fight at Dannoura.

The Minamoto fleet was superior for ships due to the competence of the sailors. Besides, many Taira soldiers betrayed, so the Minamoro clan mercilessly defeated the enemy. The members of the Taira committed collective suicide by jumping from the vessels. The result was impressive, as Leonardo Vittorio Arena explains:

“The name of the clan [Taira] vanished into collective memory. However, not the ghosts of the Taira, who haunted the coasts of Dannoura, wandering restlessly. In 1185, the war of the Gempei ended." (1)

Their epic was narrated in the book Heiche monogatari.

Ukiyoe artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi describes the battle in the woodcut At the Bottom of the Sea in Daimotsu Bay. The scene is the seabed. Taira clan leader, Tomomori is tied to an anchor with whom he plunged into the waves to die. Above all, there are many crabs tossed by the waves. They are the lost souls of the Taira samurai reborn in the form of crustaceans.

With this backdrop, full of spectres, ghosts and history, begins the animated film Inu-ô - Inu-oh - 犬 王 directed by the Japanese Masaaki Yuasa and presented in the Orizzonti section at the 78th Venice Film Festival.

Two centuries later, a boy and his father dive into the waters of Dannoura to retrieve and sell the relics of the battle between the Taira and Minamoto.

The child is happy. He can stay underwater for a long time. Unfortunately, in one attempt, the father dies and his son remains blind. Alone, the boy starts to travel aimlessly. An old musician meets him and takes him into custody, teaching him to play the Biwa. The boy changes his name to Tomona

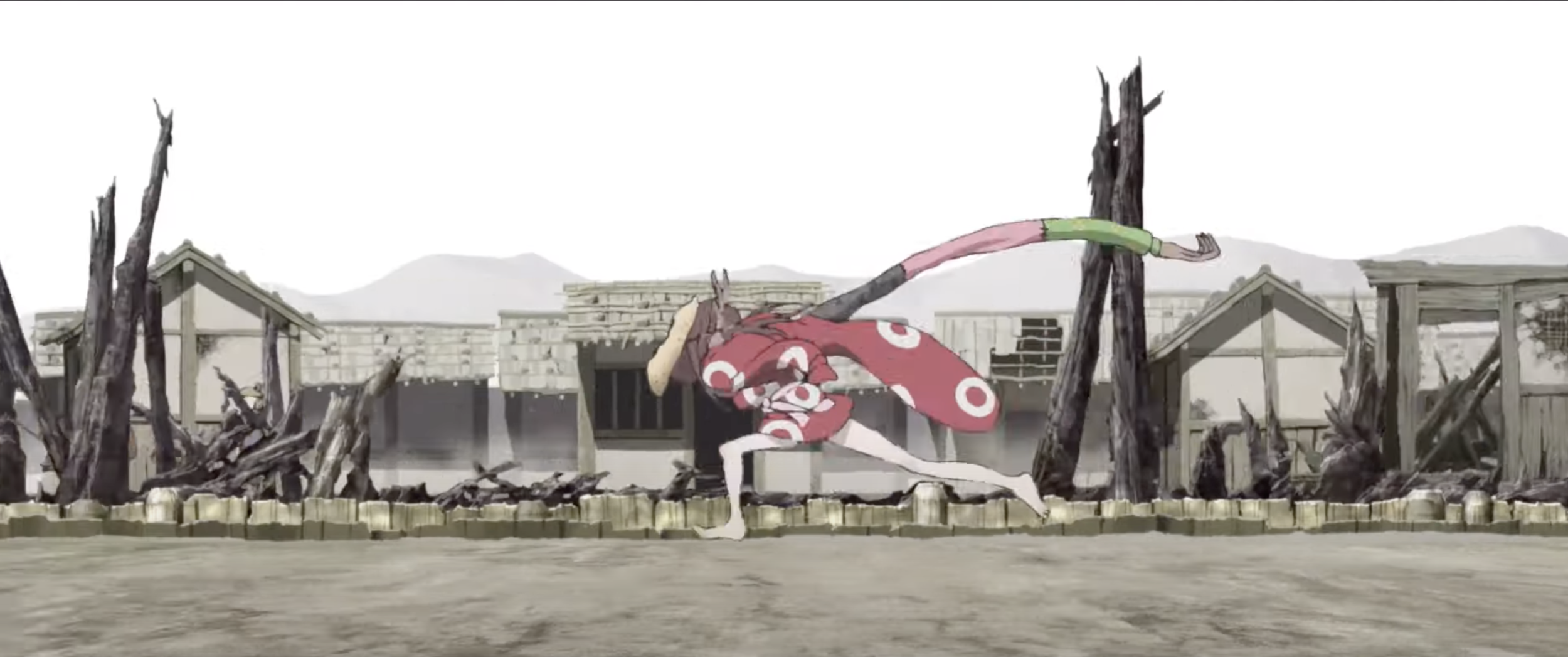

Arriving in Kyoto, he becomes friends with Inu-oh, a dancer. The face and body of Inu-oh are deformed, especially he has an abnormal arm. To hide his flaws, he is always covered with a mask.

Tomona and Inu-oh begin a spectacular collaboration. One plays and the other dances. It is an apotheosis, their performances have an audience triumph. Music and dance are overwhelming: "The desire to dance comes".

Success also creates hostility, which is forbidden by the government. It is the modernity of their art.

The director combines Japanese culture and traditions. He faces human sensitivities: coexistence with his own physical deformity, the mask, friendship, art, the Noh Theater, music.

The first reflection is on fame, on the memory of an artist's work. Why two artists on the same qualitative level, one is forgotten and the other is handed down to posterity? Masaaki Yuasa reveals the reason:

“Inu-Oh really existed, and he was a very well know artist at the time, but his legacy was lost during the course of history. At the same time, another very famous artist was the one who was remembered and many of his works were preserved, unlike Inu-Oh’s. I was interested in talking about the difference between the two.” (2)

However, to succeed, they have to fight. Affirmation is never easy for those who come from poverty:

“That theme is present, but it wasn’t my intention to be political. What I wanted to convey is how poor people struggle to change their lives. Inu-Oh was maybe forgotten, but I am telling his story with which I would like to reach as many people as possible. Nowadays, we have social networks and easy internet accessibility, but that is not enough.” (2)

A problem for the study of art and its scholars. Also, there are imaginative creators such as Masaaki Yuasa. Music is used as a bazooka for the explosion of the joy of the spectators.

The artistic concept is that of the Noh Theatre:

“Noh means 'ability', 'possibility', 'capacities', and 'talent'.

...

... combining poetry, music and dance in a medley that placed them all on the same level without favouring one or the other. The content of the wordbooks was pervaded with history and legend, with magic and fantasy." (3)

The director follows the rules. Inu-oh and Tomona are propertyless and, due to their physical difficulties, are marginalized. They don't have anything. Yet, with 'ability', 'possibility', 'capacities', and 'talent' they produce an artwork. With perseverance, they will emerge from the emptiness of their previous existence.

Tomona respected the old master of music. Inu-oh has only the desire to dance, indifferent to the insults of the family. They try to rebel against the discrimination. It is not an acceptance of their destiny, but a determined will. They are not weak. Their example is a condemnation of victimhood. Victimization does not exist in the film, perhaps a karmic feeling, but Inu-oh and Tomona refuse to be martyrs. They take the energy from their past. With their skills, they transform the cultural society around them. The strength to beat discomfort comes from their friendship and from the support of their fans. They are extravagant, but they are successful by showing positive pride.

The beauty of the structure derives from a sumptuous and deliberate false history. Did rock music exist in Japan in the 14th century? No, of course. However, the duo Tomona and Inu-oh unleash phantasmagoric songs for pace and musical tension. As if at a Madonna concert, the spectators go crazy, clapping their hands and singing the melodies.

Why the choice of rock music? The author's thought is clear:

“I decided to use rock thinking that even if it’s not authentic for the Muramachi period, it would illustrate the difference between the standard music of that time, and something new that Inu-Oh introduced into their world. He was probably not that flamboyant but because he was a very innovative performer, he probably appeared to the people of that time as something of a hard-rocker.” (2)

The motivation is artistic. The images quickly capture ancient Japan, but they are discordant with the high-sounding, modern, rhythmic, irresistible music. To which is added a sensual and rapid dance, accentuated by the disproportionate arm of Inu-oh. Intelligent structure comes from the diversity between the scenes and the music.

The first phase of the film is the presentation of the protagonists, starting with the battle of Dannoura and the ghosts on the seabed. The conflict is symbolized by the question: Will Tomona and Inu-oh be victorious? Will they defeat prejudice without appearing as victims?

The subjects face their struggle. No boats, no weapons, just ballet and melody. The antagonist is the authority of the new ruling clan. The intensity of the rhythm depends on the music and the thunderous repetition.

The characters stand out against the white background, as in the segment of the meeting between the old master and Tomona, to focus attention on their nascent affection, essential for discovering the gift of music.

Concert sequences are exemplary, appropriate for our age, and have a metaphorical value for the fourteenth century. They sound continuous, without stopping. They sing rock songs and invite the audience to applaud frantically. The singers take off their shirts during the performance and move their pelvises erotically.

Then, there is the perspective. The show, the music on the bridge and the dance are seen by Inu-oh's perspective, at the behind of his mask. Those eyes observe a phenomenal and brilliant world filled with visionary spirits. Like the ghost of Tomona's father, who reproaches his son for having changed his name. He will not be able to find him again. Phantoms can only meet known people with original names. Or like the wandering souls on the bottom of the sea of the Heicho samurai.

This view makes Japanese events dichotomous. The outside world looks different when viewed with a mask on the face. However, the mask is not a prison. The Noh Theatre has a human value meaning:

"The mask on the face shows the otherness, the actor's matrix: a still shapeless personality, which also exhibits a spirit, singing about his own passions." (3)

Again, Masaaki Yuasa follows custom and convention. Behind the mask of Inu-oh, there is a personality in formation but with unlimited passion and spirit. In the last song, he will take off his protection. Despite his imperfections, he will continue to twirl sensually: "Perhaps my beautiful face is just another mask."

In the end, the space escapes along with the stilt houses for an infinite disappearance. Both are famous, they have created an evolved style.

The director is excited, both about the return to the origins and the acceptance of traditions as a cultural basis. The representations are similar to Hiroshige's paintings. Powerful scenes, inventive colours. Using extreme long shots, then suddenly bringing the camera into close-up to capture the details of the feet.

The editing is eccentric, and the sequences change their significance rapidly.

The bright atmosphere is enhanced by stratospheric, kaleidoscopic images. Painted with golden yellow, with primary colours ton sur ton, with excessive scenography. The whole film is formal, illogical. It is not a narrative of a historical event, but it depicts Noh Theatre, and Noh Theatre is poetry.

Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Samurai. Ascesa e declino di una grande casta di guerrieri, Oscar Storia Mondadori, Milano, 2003, translated by the author

https://asianmoviepulse.com/2021/09/interview-with-masaaki-yuasa-history-is-quite-selective/

Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Lo spirito del Giappone. La filosofia del Sol Levante dalle origini ai giorni nostri, Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, Milano, 2008, translated by the author

Bibliography on the history of Japan and the Noh Theater:

Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Lo spirito del Giappone. La filosofia del Sol Levante dalle origini ai giorni nostri, Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli, Milano, 2008

Kenneth G. Henshall, Storia del Giappone, Oscar Storia Mondadori, Milano, 2005

Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Samurai. Ascesa e declino di una grande casta di guerrieri, Oscar Storia Mondadori, Milano, 2003

Gavin Blair, Samurai. Dall'Ukiyoe alla cultura pop, Nuinui, Chermignon Svizzera, 2021

Noriko Yamamoto, Ei Nakau, Bushi. Samurai leggendari nei capolavori dell'ukiyoe, Nuinui, Chermignon Svizzera, 2021

Directors: Natasha Merkulova e Aleksey Chupov

Starrings: Yuriy Borisov, Timofey Tribuntsev, Aleksandr Yatsenko

Country: Russia, Francia, Estonia

Year 2021