The Palazzo Ducale and the galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

Galleria Nazionale Delle Marche

Palazzo Ducale di Urbino

Piazza Rinascimento 13

Urbino

Credit photo: popcinema.org

In 1444, after Oddantonio's assassination, Federico da Montefeltro became Duke of Urbino.

Federico da Montefeltro transformed Urbino into one of the essential centres of the Renaissance. Federico was its patron prince.

A small town becomes the midpoint of Italian Renaissance culture.

Urbino is in a hilly and “less pleasing” area, but thanks to the "light of Italy" it shines for wisdom, erudition and art, despite the Duke's job as a captain of fortune.

Urbino

Baldassare Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier describes Urbino and its "the best of lords":

“On the slopes of the Apennines towards the Adriatic sea, almost in the centre of Italy, there lies (as everyone knows) the little city of Urbino. Although amid mountains,and less pleasing ones than perhaps some others that we see in many places, it has yet enjoyed such favour of heaven that the country round about is very fertile and rich in crops; so that besides the whole- someness of the air, there is great abundance of everything needful for human life. But among the greatest blessings that can be attributed to it, this I believe to be the chief, that for a long time it has ever been ruled by the best of lords; although in the calamities of the universal wars of Italy, it was for a season deprived of them. But without seeking further, we can give good proof of this by the glorious memory of Duke Federico, who in his day was the light of Italy ...." (1)

Every Renaissance Lord needs a palace. Federico da Montefeltro wanted to build one of the most personal residences. Federico chose Luciano Laurana as the architect, then was replaced by Francesco di Giorgio.

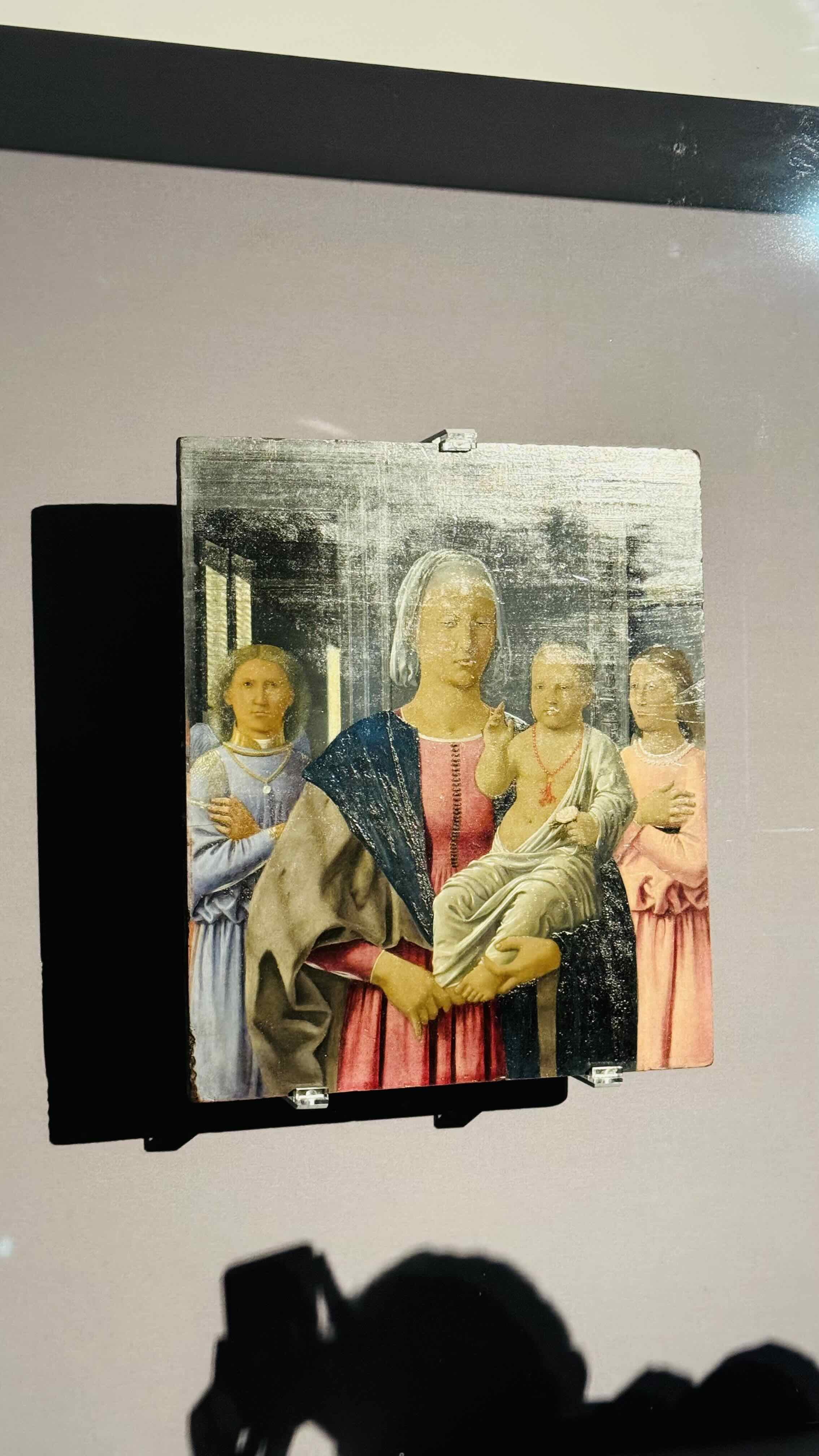

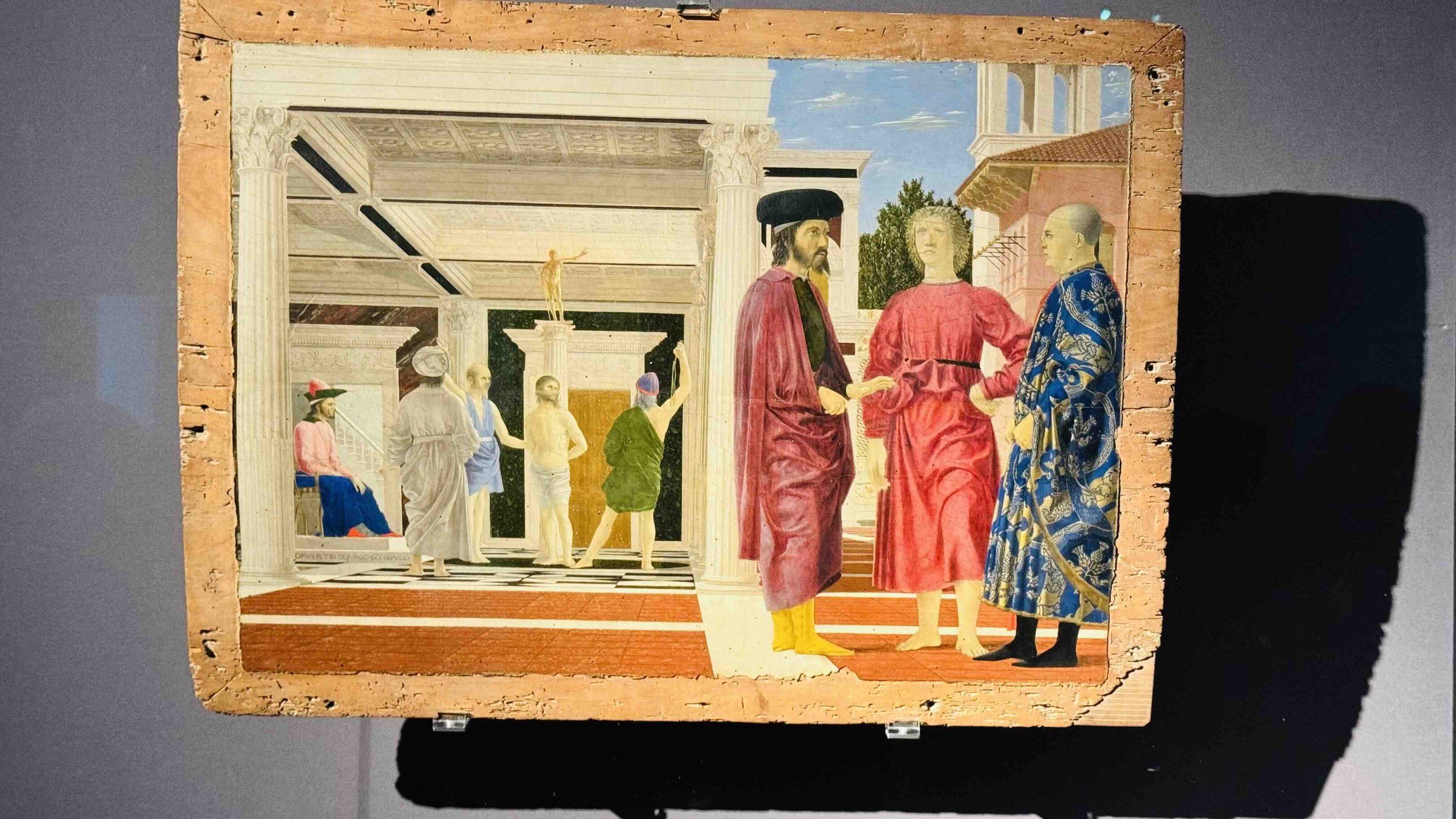

Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ (La flagellazione)

The Palazzo Ducale is inimitable, "the most beautiful to be found in all Italy".

Baldassare Castiglione exalts its infinite beauty:

“Among his other praiseworthy deeds, he built on the rugged site of Urbino a palace regarded by many as the most beautiful to be found in all Italy; and he so well furnished it with everything suitable that it seemed not a palace but a city in the form of a palace; and not merely with what is ordinarily used,—such as silver vases, hangings of richest cloth-of-gold and silk, and other similar things,—but for ornament he added countless antique statues in marble and bronze, pictures most choice, and musical instruments of every sort, nor would he admit anything there that was not very rare and excellent. Then at very great cost he collected a goodly number of most excellent and rare books in Greek, Latin and Hebrew, all of which he adorned with gold and with silver, esteeming this to be the chiefest excellence of his great palace.” (1)

Giorgio Vasari confirmed the same enthusiasm in his book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architectswhen he wrote about Francesco di Giorgio:

“He had very good judgment in architecture, and proved that he had a very good knowledge of that profession; and to this ample testimony is borne by the palace that he built for Duke Federigo Feltro at Urbino, which is commodiously arranged and beautifully planned, while the bizarre staircases are well conceived and more pleasing than any others that had been made up to his time. The halls are large and magnificent, and the apartments are conveniently distributed and handsome beyond belief. In a word, the whole of that palace is as beautiful and as well built as any other that has been erected down to our own day.

Francesco was a very able engineer, particularly in connection with military engines, as he showed in a frieze that he painted with his own hand in the said palace at Urbino, which is all full of rare things of that kind for the purposes of war.” (2)

"The Ideal City

At the time, the main road to Urbino was from Florence. After crossing the Apennines, travellers arrive in Urbino. They could see an impressive spectacle, not a heavy construction, with excessive military towers. The first vision was of delicate, elegant, slender little towers:

“Even the front of the slender towers, which recalls its medieval soul better than any other part, shows in the graceful towers more than an affirmation of strength and threat, a static and ornamental motif, enriched by the vast breadth of the loggias, on which the victorious eagle of Montefeltro seems to rise as dominant not only of the small glorious city but, beyond the solemn undulation of mountains that surround it with an inviolable fortress, of the portentous deployment of Italian civilization.” (3)

Furthermore, Federico led the court in a strict manner. Federico was a man of virtue, respect and moderation reigned in the palace. This is how Vespasiano da Bisticci narrates the Lives of Illustrious Men of the 15th Century:

“As to the ruling of his own palace, it was just the same as that of a religious society: for although he was called on to feed at his own expense five hundred mouths or more, there was nothing of the barrack about his establishment, which was as well ordered as any monastery. Here there was no romping or wrangling, but everyone spoke with becoming modesty.” (4)

Raphael, Portrait of a Young Woman (La Muta), 1506 1508

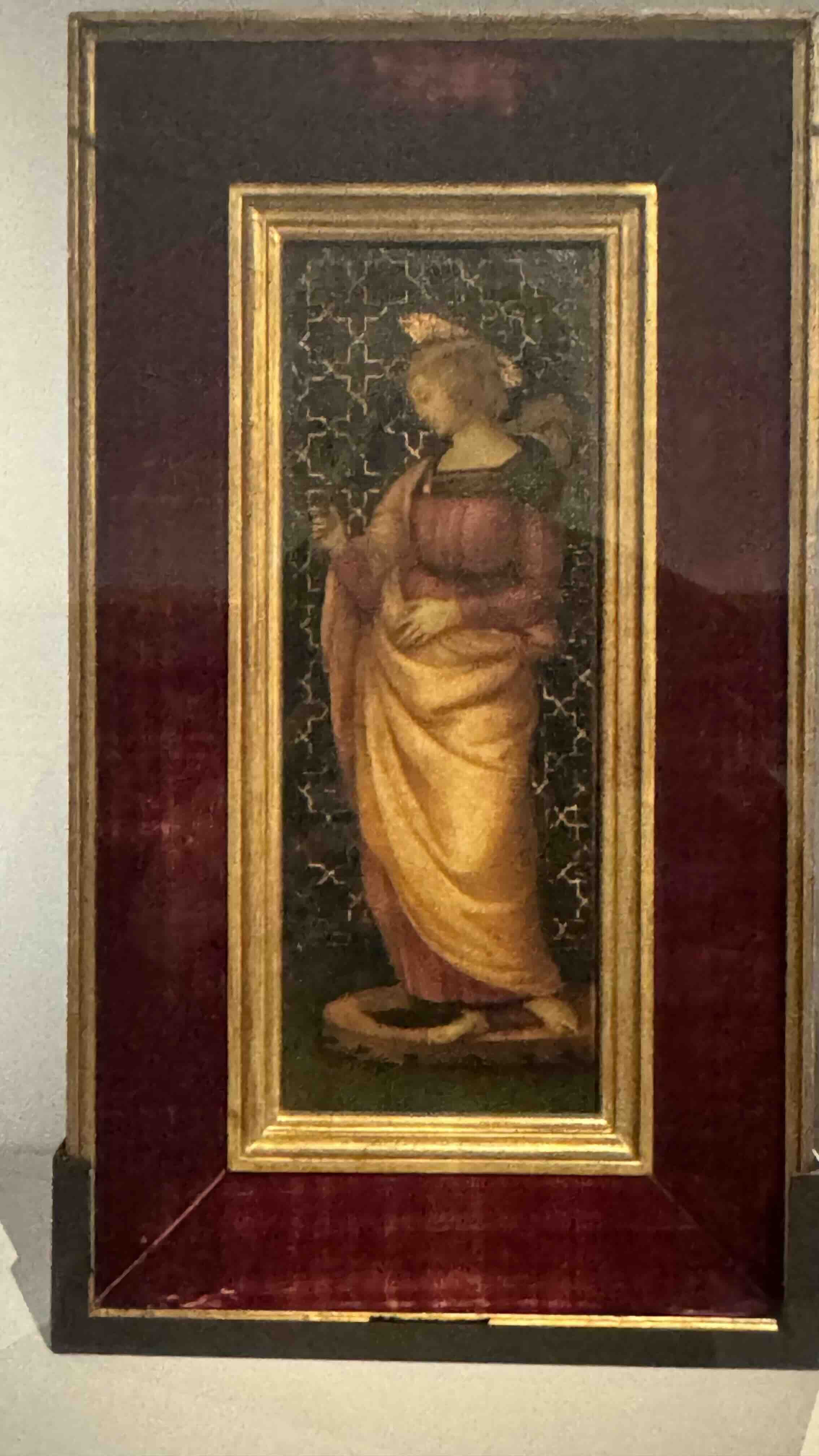

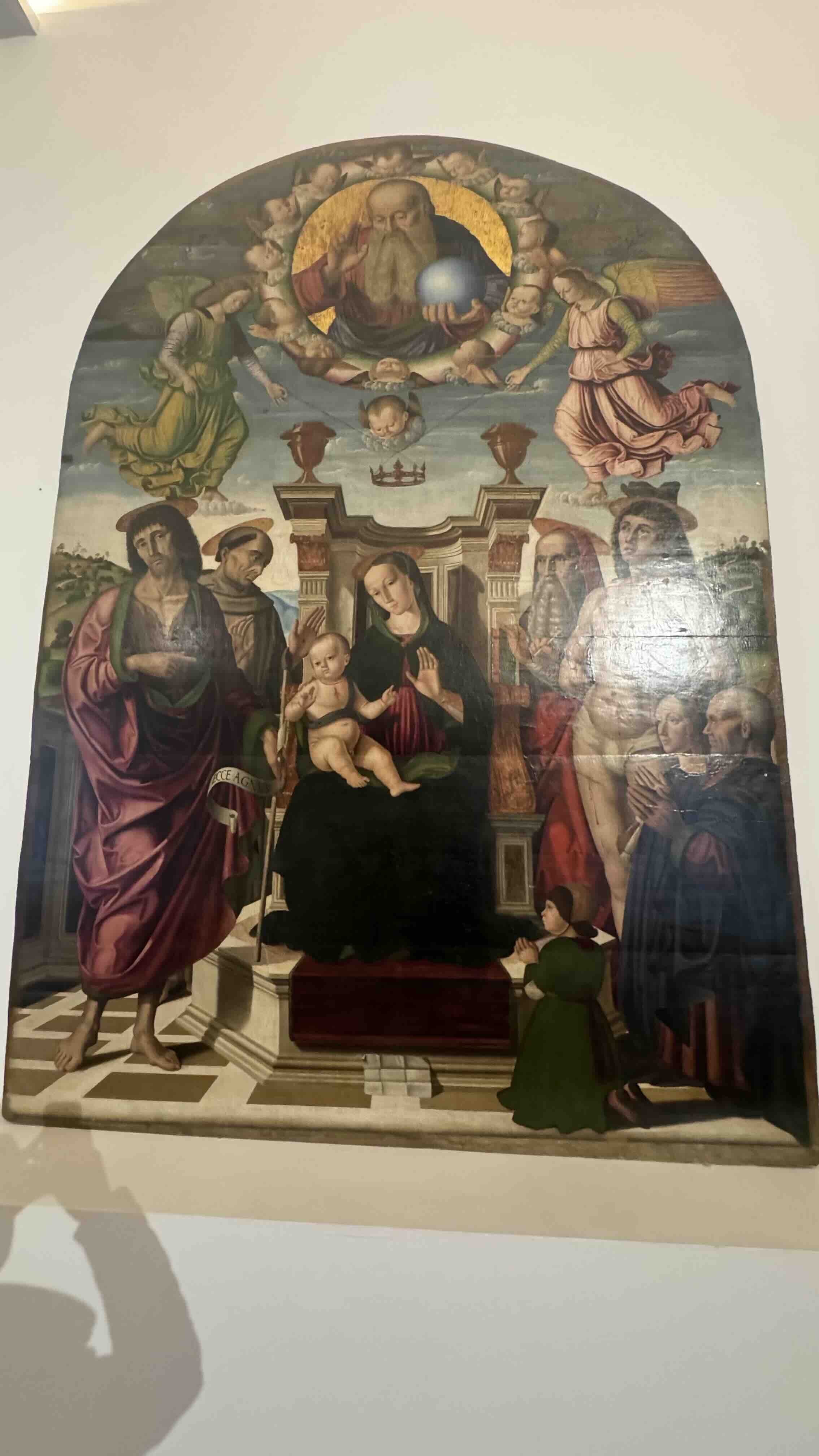

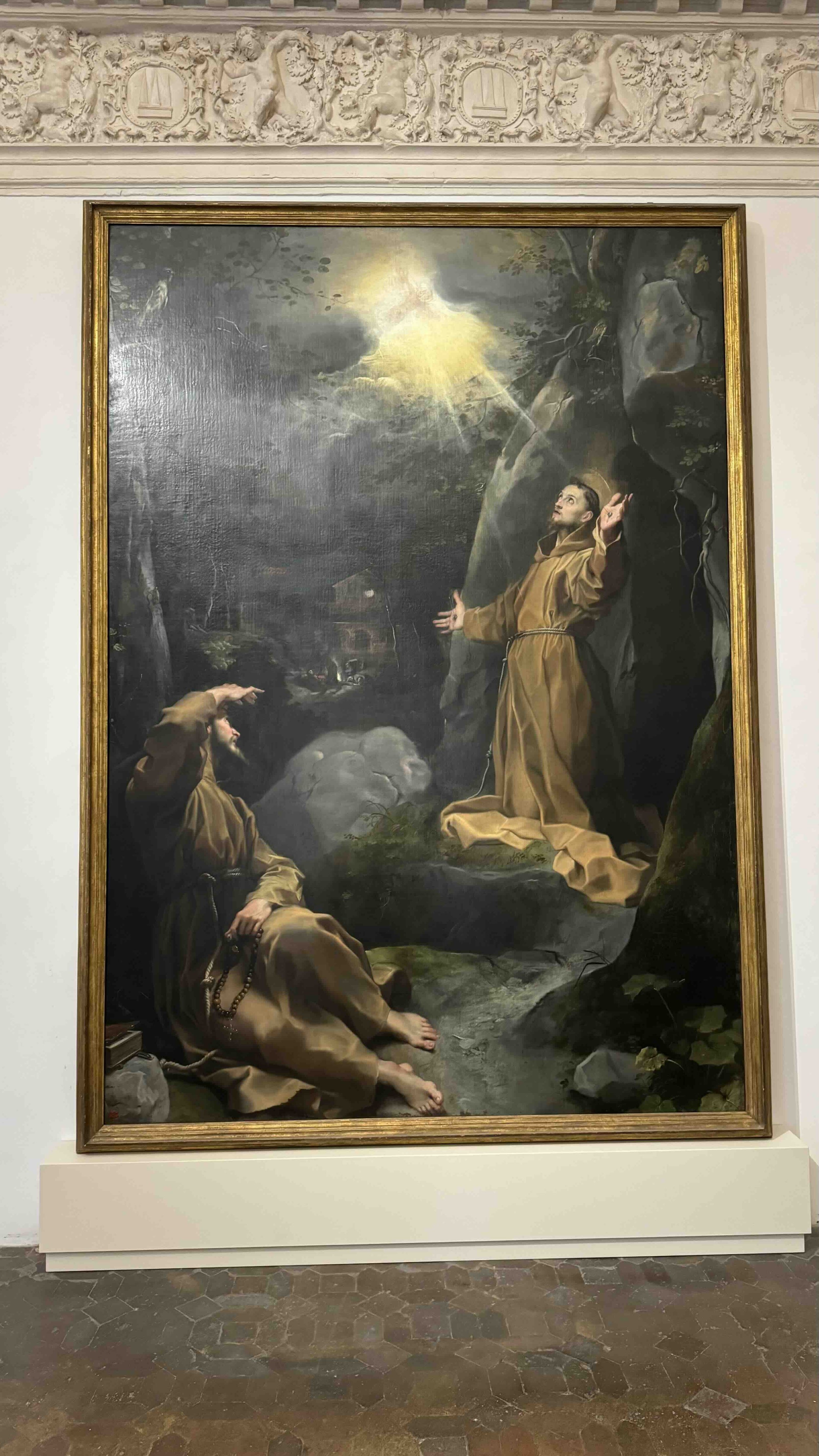

The "bizarre staircases are well conceived and more pleasing", the "halls are large and magnificent", the "graceful slender towers", and “everyone spoke with … modesty" were the perfect and ideal environment to welcome illustrious guests and glorious artists. They studied, talked, dialogued, discussed, painted in Urbino in the fifteenth century: Raffaello Sanzio, his father Giovanni Santi, Donato Bramante, Paolo Uccello, Piero della Francesca, Melozzo da Forlì, Baldassare Castiglione, Luciano Laurana, Giusto di Gand, Pedro Berruguete, Fra Diamante, Leon Battista Alberti, Luca Pacioli, Luca Signorelli, Torquato Tasso.

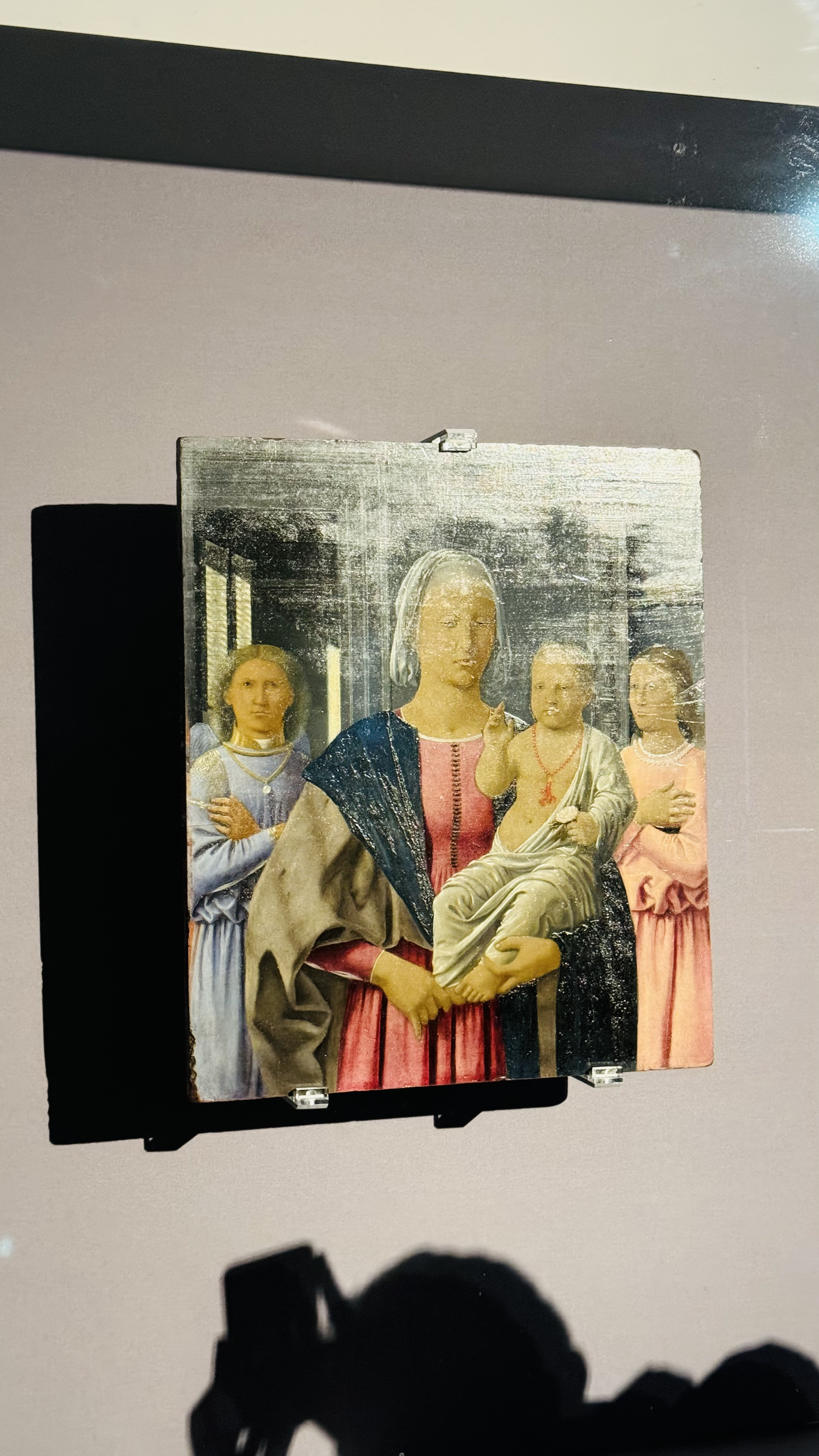

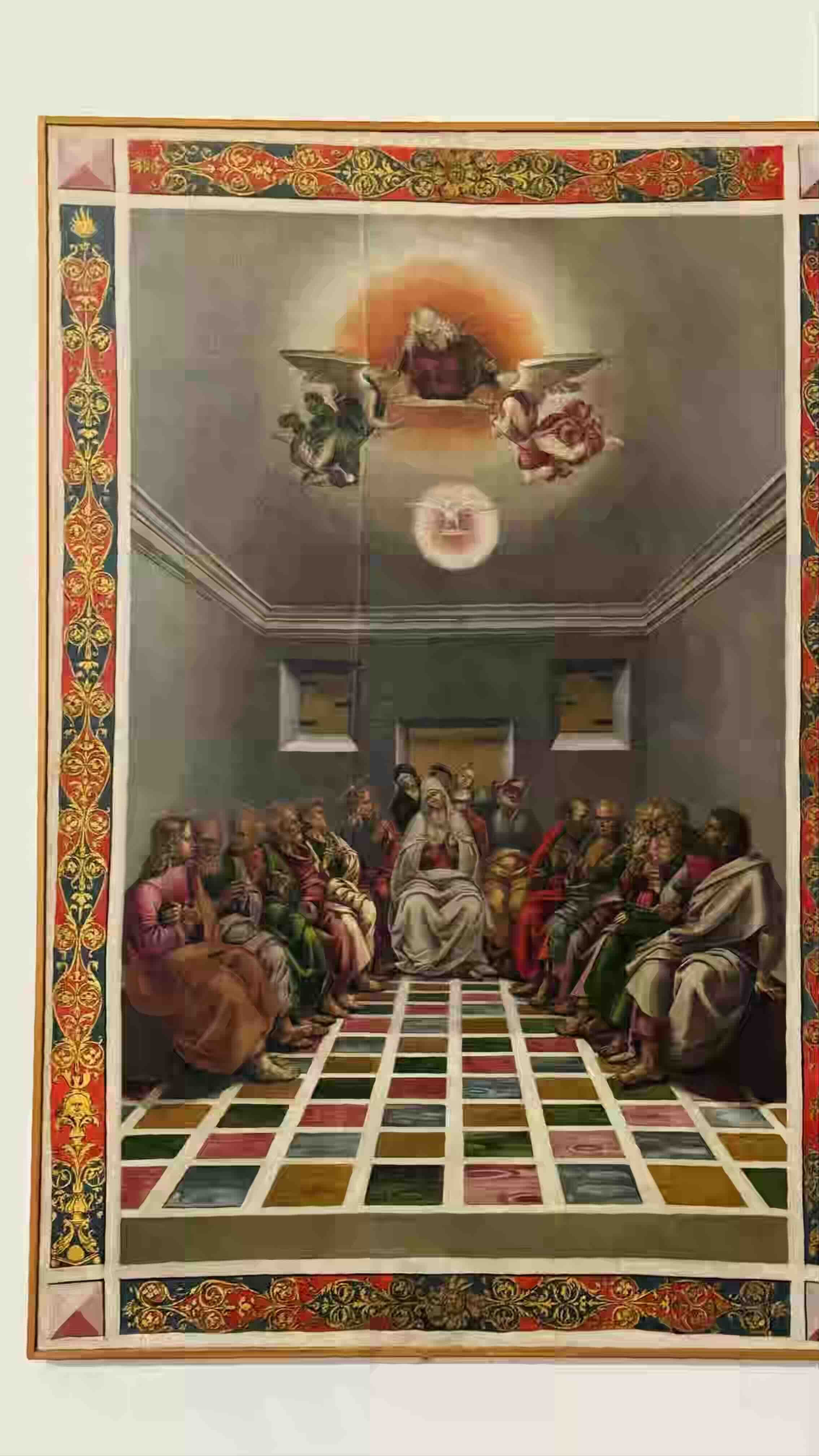

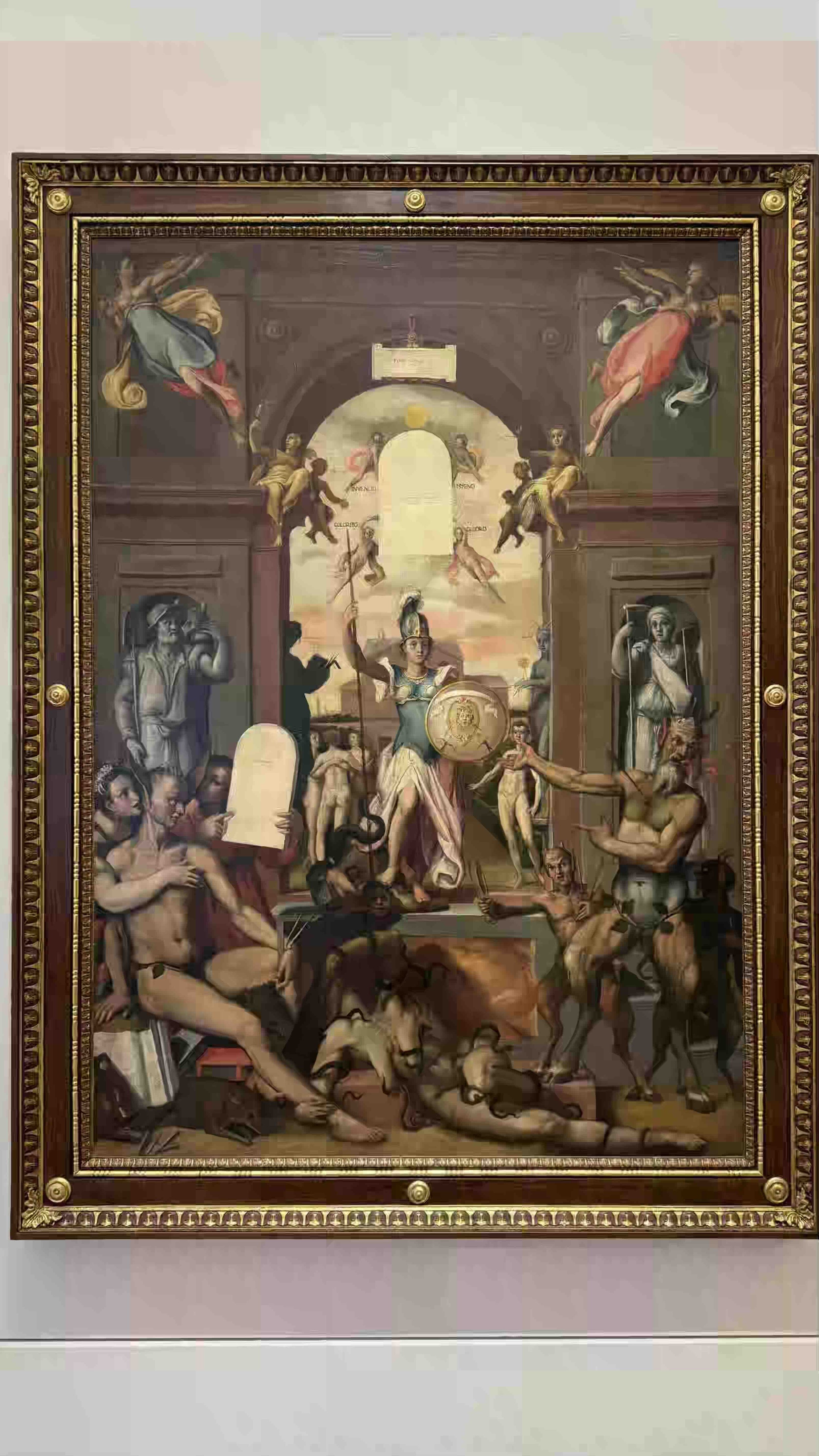

The architectural union, the artistic culture, the personality of Federico da Montefeltro are the peculiarities and make the Ducal Palace of Urbino the ideal place to establish the National Gallery of the Marche.

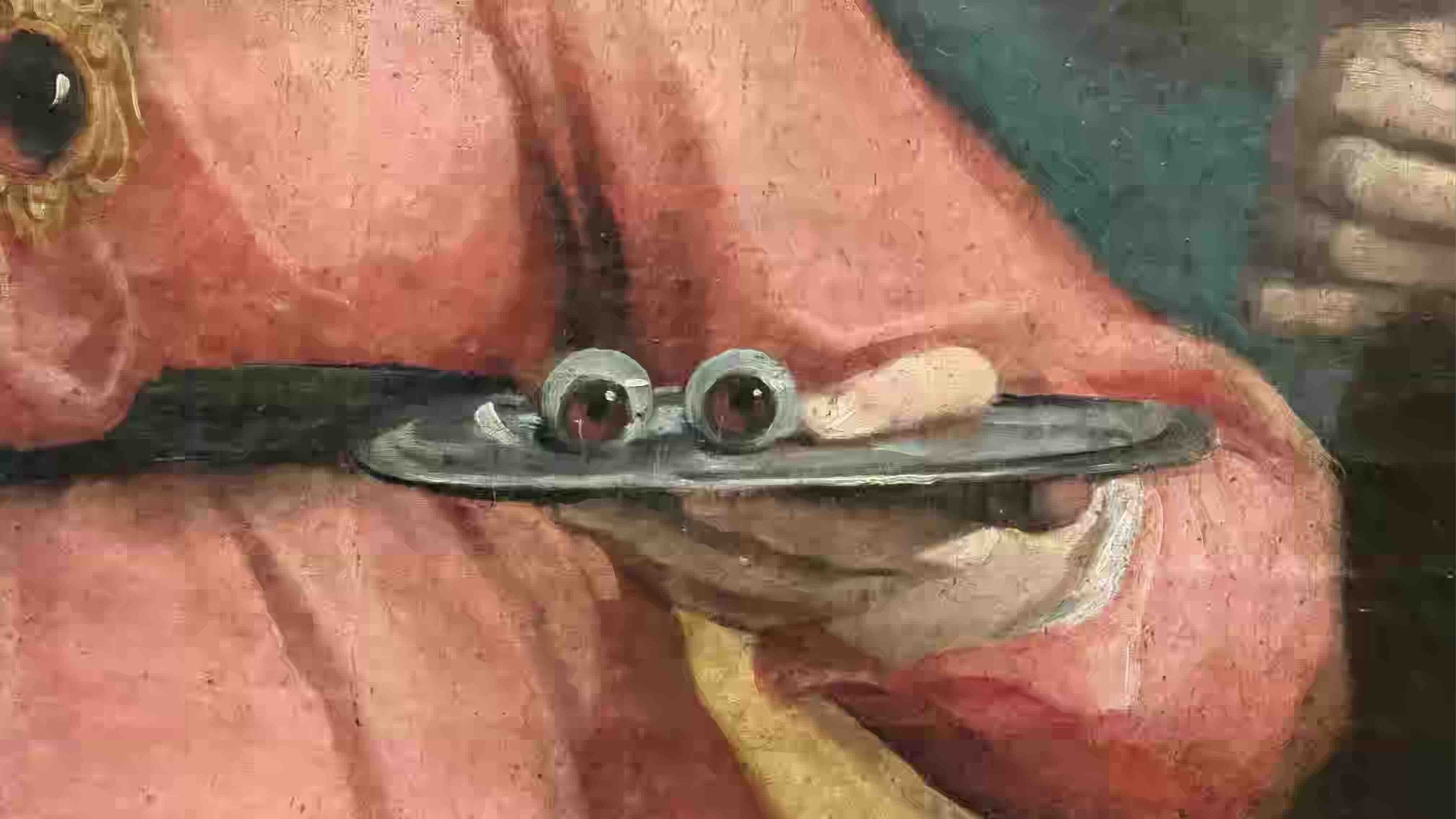

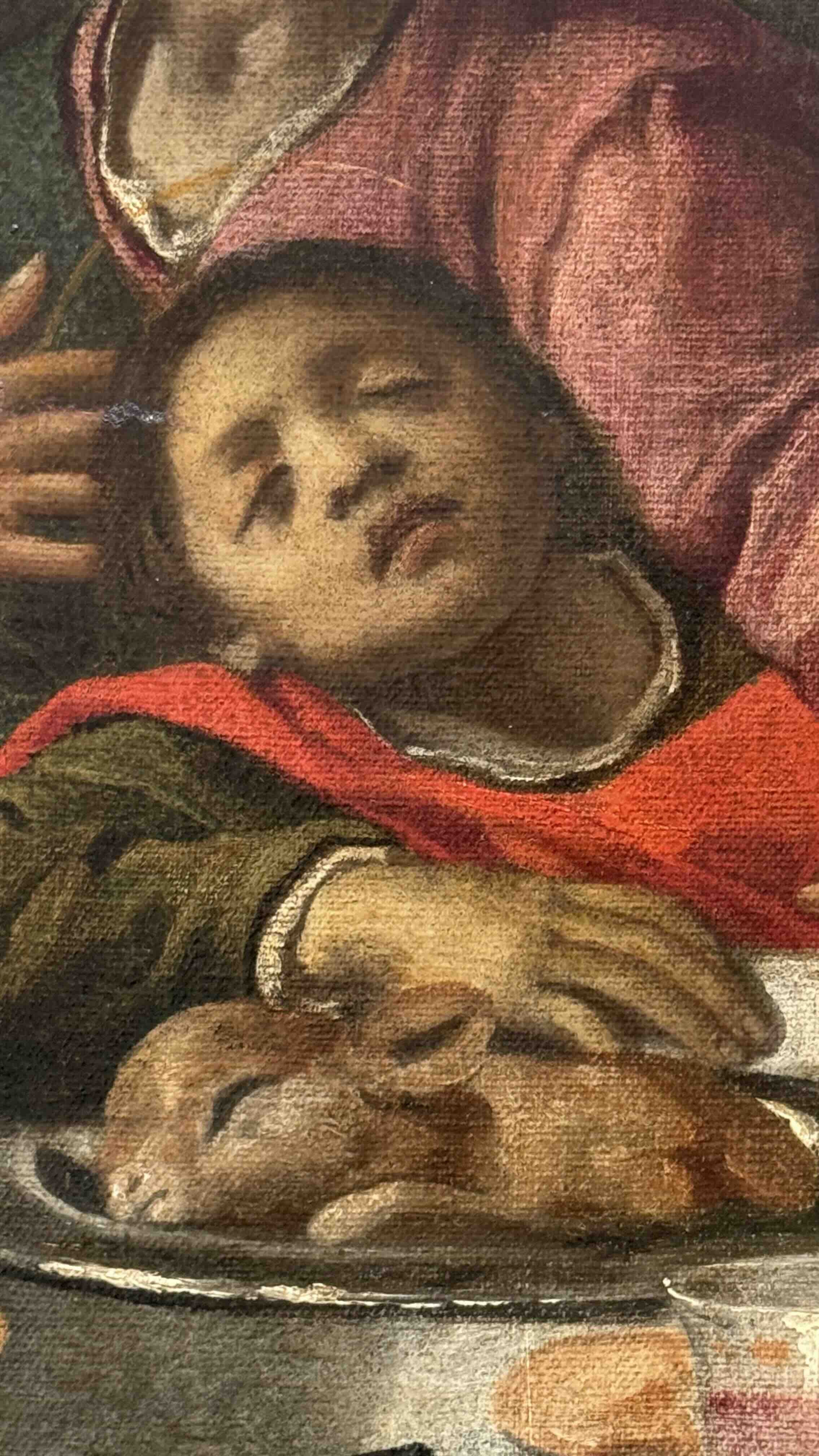

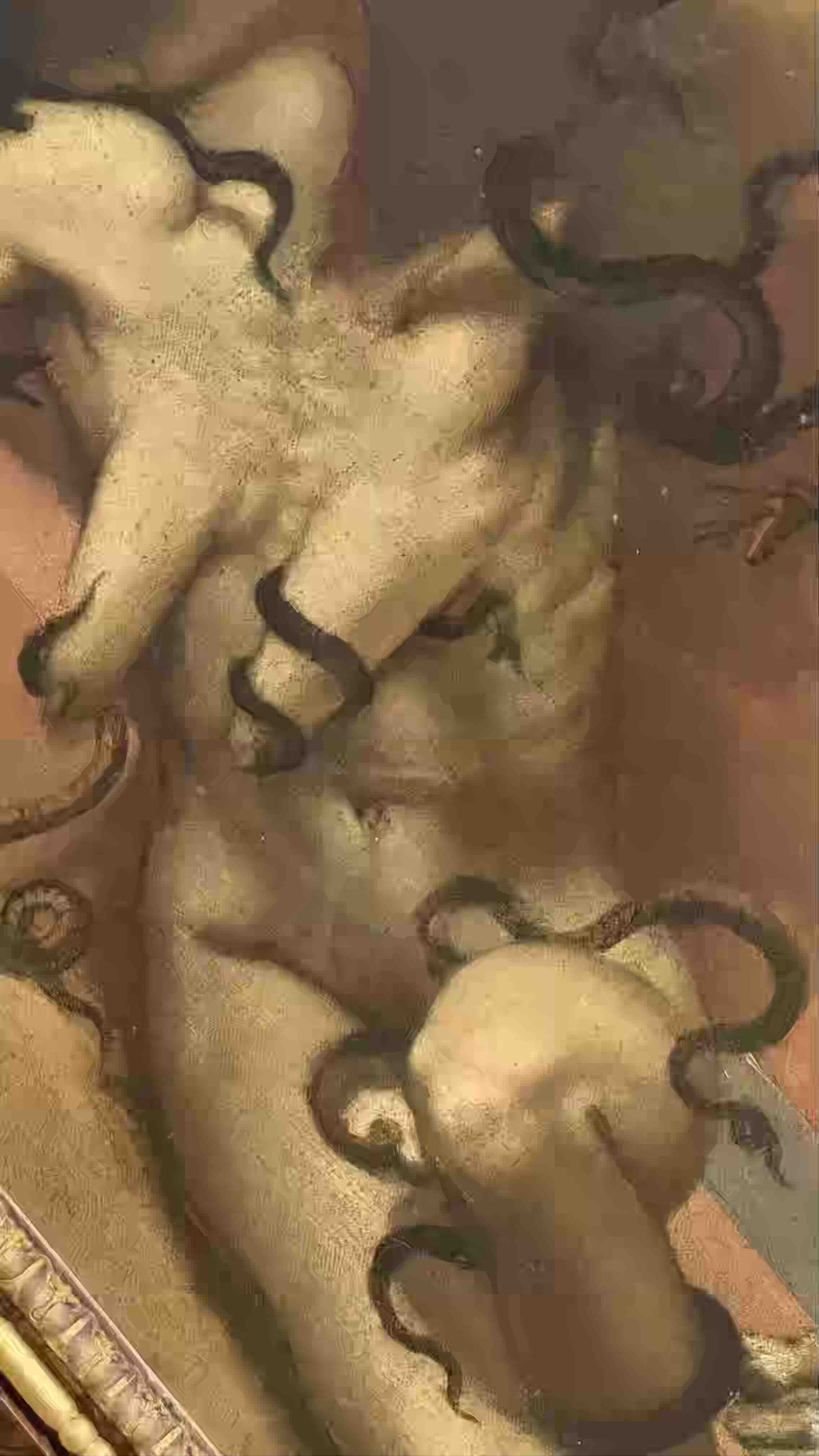

Inside, there are exclusive artworks, an unforgettable treasure chest for the history of art.

Baldesar Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1901

Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Luigi Serra, Il Palazzo Ducale e la Galleria Nazionale di Urbino, La libreria dello Stato, Roma, 1930, Anno VIII, pag. 6 https://www.google.it/books/edition/Il_Palazzo_ducale_e_la_Galleria_nazional/wMQtAQAAIAAJ?hl=it&gbpv=1&dq=storia+del+palazzo+ducale+di+urbino&printsec=frontcover translated by the author

Vespasiano da Bisticci, Lives of Illustrious Men of the XV Century, Harper Torchbooks, New York, pag. 106 https://archive.org/details/renaissanceprinc0000vesp_n6z3

Bibliography:

Denis Mack Smith, Federigo da Montefeltro, Quattroventi, 2005

Is narcissism a primary quality for an artist?

Without narcissism, could an artist experience aesthetic and poetic stimuli?

According to the elegant exhibition The Portrait of the Artist. In the Mirror of Narcissus. The Face, the Mask, the Selfie - curated by Cristina Acidini, Fernando Mazzocca, Francesco Parisi, and Paola Refice at the Museo Civico San Domenico in Forlì - the answer is definitive: narcissism is an undeniably and irrefutably inspiring genius.