Yurt - Dormitory Directed by Nehir Tuna

Yurt - Dormitory

Directed by Nehir Tuna

Starrings: Doğa Karakaş Can Bartu Arslan Ozan Çelik Tansu Biçer Didem Ellialtı Orhan Güner Işilti Su Alyanak

Ahmet Hakan Yakup Hodja Father Mother Behlül Hodja Sevinç

Country: Turkey

Year 2023

Review Author: Roberto Matteucci

Click Here for the Italian Version

“Not everything Arab is sacred.”

In Turkey, in the 1920s, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, an army officer, unleashed the challenge to the decadent Ottoman Empire from Anatolia. His motivation was no longer religious. His principles were secularism, patriotism, and the Westernisation of society. With his victory, Turkey became a Muslim country with a lay leader. The two factions regularly faced in violent confrontations. A vigorous Muslim opposition contested the Kemalist republic. There were numerous revolts, such as those of the dervishes and other brotherhoods.

“During the sixties and seventies, these militant religious organizations seemed to have lost ground, and in many countries, their activity was prohibited or subject to restrictions; however, they continued to operate clandestinely and were in synchronicity with the tendencies and desires of many members of the lower classes of Islamic society." (1)

Seculars and religious still fight nowadays. A war with alternating victories and defeats, in a divided Türkiye. In the era of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, religious brotherhoods have acquired an advantage but certainly not an evident predominance.

In 1996, this competition was temporarily won by the secular. They dominated schools. In educational institutions, young religious people were viewed with repulsion. It is the historical period of the film Yurt – Dormitory by director Nehir Tuna presented at the 80th Venice Film Festival.

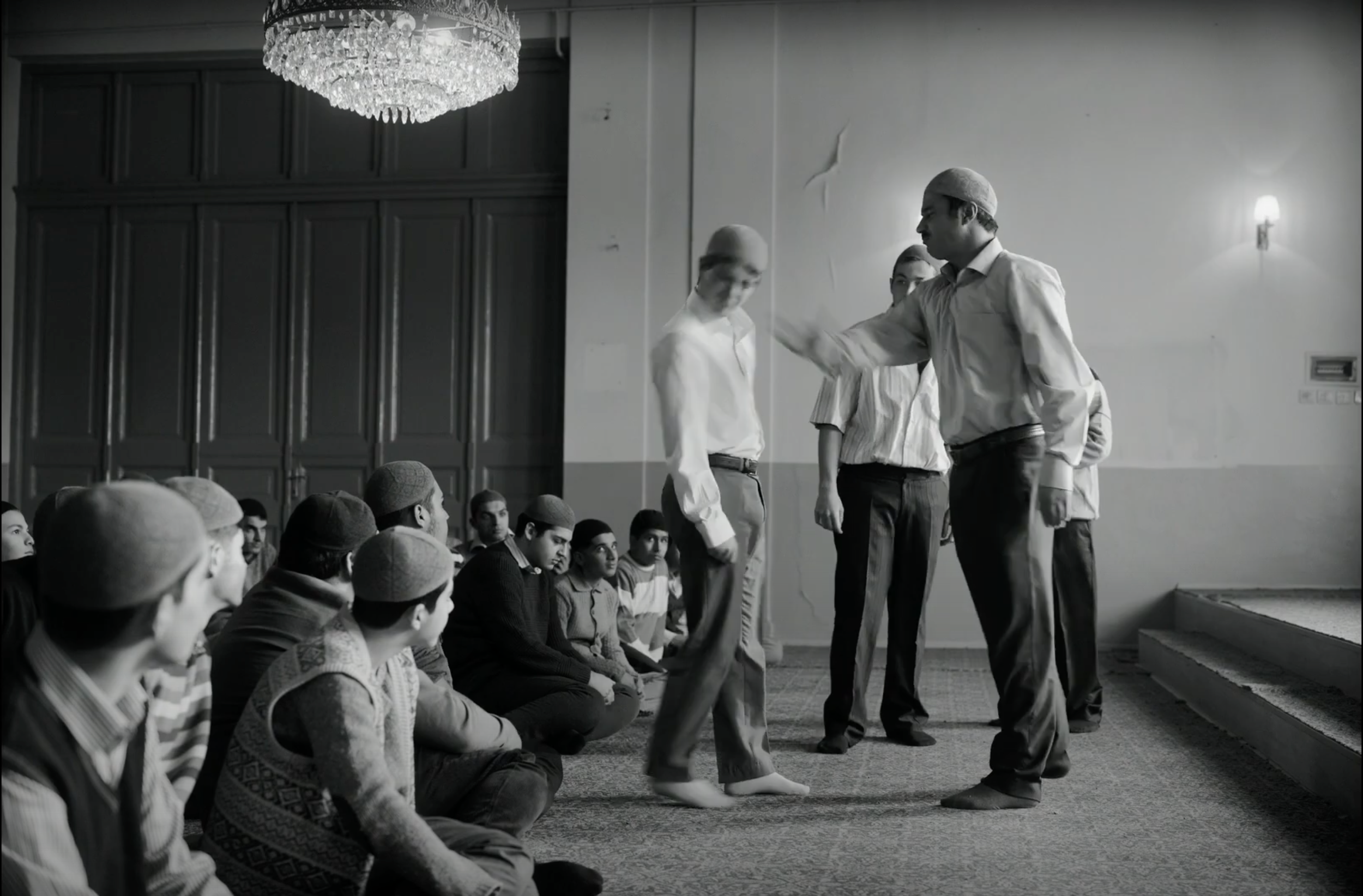

The Yurts, dormitories run by brotherhoods with an intensely religious spirit, were in dispute with the lay schools. They were in contrast to the system of secular government.

Ahmet is a teenage student. He is from a deeply spiritual family, with a father who was a member of an influential congregation. He studies in a lay school but simultaneously sleeps in a Yurt. He is ashamed of his condition in front of his classmates. He does not reveal it, so he gets out by bus far from the Yurt.

Likewise, the dormitory hides its non-religious aspect, often coming into conflict with strict rules.

There is also a social component. The school is attended by children of the middle class, a rising bourgeoisie that grew up thanks to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's politics.

The guests of the dormitory are instead young people from more disadvantaged and needy families.

Ahmet becomes friends with Hakan, an orphan welcomed into the hostel.

Nehir Tuna was born in 1985 and is the same age as the protagonist. He had similar experiences, staying in the Yurts. In an interview, he states his autobiographical influences:

“Just like Ahmet, the main character, I’ve spent five years in a religious boarding school. I keep abiding memories of this experience, and most of them are quite similar to what Ahmet is going through: being brutally separated from one’s family, having to get used to new living conditions overnight... The reasons why my father wanted to send me to a boarding school are also addressed in the film: to climb the social ladder, to assert his faith and his religious responsibilities, to set himself up as an example within the community... Ahmet’s father is seeking his own salvation by sending his son away.

Just like I was, Ahmet is a hard-working student, who doesn’t rebel much and who wants to please everyone, especially his father. He is also really resilient: he knows that time will prove him right.” (2)

The author describes these arguments. The primary one is the quarrel between lay people and believers and others of equal depth.

“Being brutally” it seems that the director felt the first distance from his family intimately. He says:

“... being brutally separated from one’s family, having to get used to new living conditions overnight.” (2)

Many sequences emphasize the family and, mostly, the conflict with the father. Discussions between daddy and son even culminate in a bloody clash: Ahmet wounded the parent. An obvious Oedipal complex.

Throughout the film, the director describes his love, both family and with his friend Hakan, as well as with his classmate, whom Ahmet courts:

“How would you describe the relationship between Ahmet and Hakan? Is it a love story?

All relationships are multifaceted, and sometimes it just take a different outlook to change the nature of a bond. Overall, I think that Yurt is the story of a young boy who is searching for love: the love of his father, or the -more classically romantic- love of the young girl who joins his class during the year, or that, more friendly, between him and Hakan, whom he sees at once as a model, a big brother... To me, Ahmet’s story is a combination of those three relationships. And maybe he gradually realises that his relationship with Hakan features all these aspects: filial love, romantic love, friendship/love.” (2)

It is a common attitude of a teenager, a coming-of-age story. Set in a dramatic era, in a nation that is economically growing but with many social difficulties.

In his interview, Nehir Tuna talks about friendship, love and even homo impulses experienced by Hakan with an intransigent and fervent teacher.

Ahmet's entrance into the school is the significant initial scene. All comrades' shoes are old, broken and dirty. His shoes, meanwhile, are shiny and very clean. Despite coming from a rich family, emphasised by his luxurious house, Ahmet is solitary. He faces hostile environments and contexts with his authoritative father or secular classmates or with the love of a girl. He appears immature despite his intelligence and his attention to studying. He does not know how to extricate himself from the two worlds. He loves and accepts both.

In the end, he made a choice. To reach his goal, he had to involuntarily crush his close friend, the weakest person, sacrificing him for his wishes.

Hakan has no family and no home. Without the dormitory, he would be homeless. He seems interested in teacher Hodja's religiosity but in reality, he just follows his hormonal impulses. It is not a divine choice. He tries to flee from his loneliness.

Ahmet and Hakan are different. Ahmet's parents are wealthy. Hakan is poor and orphaned. Ahmet lives in a comfortable house, surrounded by the affection of his father and mother. Hakat is in a loveless dormitory. Ahmet learns profitably and slowly approaches religiosity. Hakat is strictly religious, needing an alternative to the void in which he is immersed.

Their friendship is a turning point in both their lives. The basis is a chimaera, a treasure hunt, a hope without reality. It will be their expedition to find a lost treasure, with a stolen car, that establishes their attachment and their unsolvable diversity.

However, there is an imbalance. Hakan has a personality more evil than good, but at the same time, he is more sincere and genuine. Hakan is attracted to his friend but suffers from hidden envy. He steals his shoes and other items to sell on the black market. He is fragile, insecure, unstable, melancholic.

These characteristics emerge clearly during their attempt to recover the treasure. Both have the conviction and desire to be emancipated. Yet, there is a fundamental disparity. Ahmet has his back covered, he loves it as an adventure. Behind him, he has a wealthy family ready to help him even in case of trouble.

Hakan's situation is different. He risks his life, his future. He has only one chance, so he has to challenge his luck. Failure would be the end: expulsion from the dormitory and being homeless.

The conclusion reveals Ahmet's selfishness as he remains indifferent to his friend's needs.

The filmmaker deliberately uses various languages in black and white:

“Yurt starts in black and white and then, mid-course, it switches to colour. What was the motive for this bold move?

Symbolically, I thought that black and white suited life at the boarding school: everything in there is unequivocal, it is either all black or all white. You are either a devout person or an infidel, there is no room for nuance. There is no room for colour either, especially for the mixing of colours. Colours only appear when Ahmet and Hakan run away and experience a true feeling of freedom. The film becomes more dynamic, the camera is more mobile, and freer as well... Then the colours slightly fade out as the film draws to an end.” (2)

It is a Truffault film, both for the beauty of black and white and for the adolescent story of eternally problematic growth, tormented between the love of the father and that of friends.

Black and white suddenly disappear. Colour comes back. It is time to escape. The guys feel falsely free. They have the adrenaline and rebellion of teenagers. It constitutes a revolt against all, both secular and religious entities. Therefore, colour paints the dream of the two friends because life can be black and white but people always dream in colour.

The film focuses on the daily and meticulous existence in the dormitory. It is not easy to live there. Too many differences, too much discipline, too many prohibitions, too many bullies. The roommates are inhibited. So they react. Quarrels, fights and even a strong sexualty. Roommates enjoy viewing pornographic images, they try to survive..

The father has gone out, Ahmet is at home, in bed. Look for the pillow on which the father slept. He takes it and sleeps on it. An expressive, passionate but obvious sequence. It is not a normal generational fight but it is an impetuous request for love. In the epilogue, the father is proud of his son. Hakan is missing, injured during the escape, probably living on the streets. Ahmet knows what to choose.

Secular and religious disagreements are fierce. The dormitory is shocked by the police searches. But the police know that they cannot find anything. Their only purpose is to terrify the hosts.

Besides, they are also threatened by people of the laical movements. This difficult situation still exists in a Turkey eager for pan-Islamic dominance.

The viewer remains doubtful. They expect the opposite, namely, fundamentalists who attack secularists, not knowing the powerful developments of Turkish history.

Not even the secular and bourgeois school is a paradise. “It's scary there is someone like that among us” Ahmet's girlfriend declares her fear for the presence of Yurt students in the school. The girl is unaware of Ahmet's truth. It is a discrimination against individuals with a religion. Ahmet hides his existence. The reason is love. He loves his girl classmate, he loves his parents and he loves his rebel friend.

The director is smart. An aesthete of beauty, using colour and photography like a painter. Black and white has some sensible nuances, constantly following the characters and their evolution. Their glances, the allusion, are minimal gestures of the body and eyes.

The structure is clear. The steps of the plot are precisely outlined. The final twist in Ahmet's decision is integral to his development.

The film has an atmosphere, formal, poetic, elegant chromaticism, an ethical hesitation for ambiguous behaviours.

Bernard Lewis, La costruzione del Medio Oriente – The Shaping of the Modern Middle East, Edizione economica Laterza, II edizione, 2011, Pages 144/145 Translated by authour from Italian

Director’s Interview. Pressbook.

Revenge and forgiveness belong to three Mexican boys intent on organizing their retaliation in the film A cielo abierto - Upon Open Sky by directors Mariana Arriaga and Santiago Arriaga presented at the 80th Venice International Film Festival.