Prague, the real city

Kampa Island

Prague, the real city

Author: Roberto Matteucci

Credit photo: popcinema.org

In Prague, only the imagination remained. It is a city to imagine. Let's imagine Prague during the Medieval era, imagine the dark streets, imagine the cold winter, imagine the mist, imagine the empty alleys, imagine the strange noises in the silence, imagine this gloomy atmosphere combined with the traditions of own religion.

Unfortunately, today's Prague, for romantic dreamers seeking alchemical fumes, is overrun by barbarians. If the fog lifted, one could even glimpse, on the slopes of Mala Strana, the ancestral figures sculpted with alchemical gold produced in the Golden Lane.

Praga, Prague, Mala Strana and the Castle

In Mala Strana, if one were lucky, one might find honest, modest, generous, patriotic, devoted, wise, cunning persons. Restaurants, bars, clubs and pastry shops have replaced taverns, inns, and brothels. Branches of escape paths from the subsoil can also be found under them. They have caves, caverns, cellars, catacombs on which they are built.

Between the roads, palaces, churches, it is hardly distinguishing the picturesque, colourful, lively Jan Neruda's protagonists. There is apprehension when meeting them:

“... the citizens of this neighbourhood didn't seem very calm and quiet.” (1)

Jan Hus monument in Old Town Square

They are two men, engaged in eating pork hocks and sausages, sitting at the restaurant table. Perhaps they are Mr Ryšanek and Mr Schlegl. For years, they drank beer at the same table without talking to each other.

Or, they are the voices coming from above, perhaps from the roofs. Perhaps, they are Kupka, Hovora, Novomlynsky, Jakl while confiding in non-existent and impossible love:

"But I hope he hasn't offended his best friends by marrying an ugly woman!" (2)

Or looking at the courtyards inside the buildings, one wonders if the student prosecutor, Dr Krumlovsky is facing a horde of weirdos, bizarre, chatty, agitated, adulterers, deaf, talkative, noisy, restless, false witnesses, failed painters, beaten children and absurd duels.

Or, it is the dream of the immense St. Vitus Cathedral at night. It is time for the mass celebrated by St. Wenceslas.

“Malá Strana doesn't seem to look at the Castle, and it doesn't even look at the river.” (3)

Therefore, it is necessary to reach the Vltava River to examine the clay banks. The river is three hundred and thirty-three kilometres long. At night, lashed by wind, frost, rain, snow, one needs to walk along the towpath if one wanted to secretly scrutinize, thanks to the magic of the Kabbalah, the ceremony for making a pile of clay come alive, who will shock the nearby ghetto with an impetuous figure ready to defend the many synagogues:

“Create a clay Golem and annihilate the evil Jew-eating rogue.” (4)

The Rabbi decided to follow the instructions. At midnight, they went to Vltava bank. They took clay and forged the body of a man. Esoteric practices followed occult rites and the three elements - fire, water, air - allowed the fourth element - the earth - to transform the clay into a living being.

Crossing the Charles Bridge, one arrives in the old city. Not far away is the Josefov district, with its remnants of the Prague Jewish ghetto: the synagogues and cemeteries.

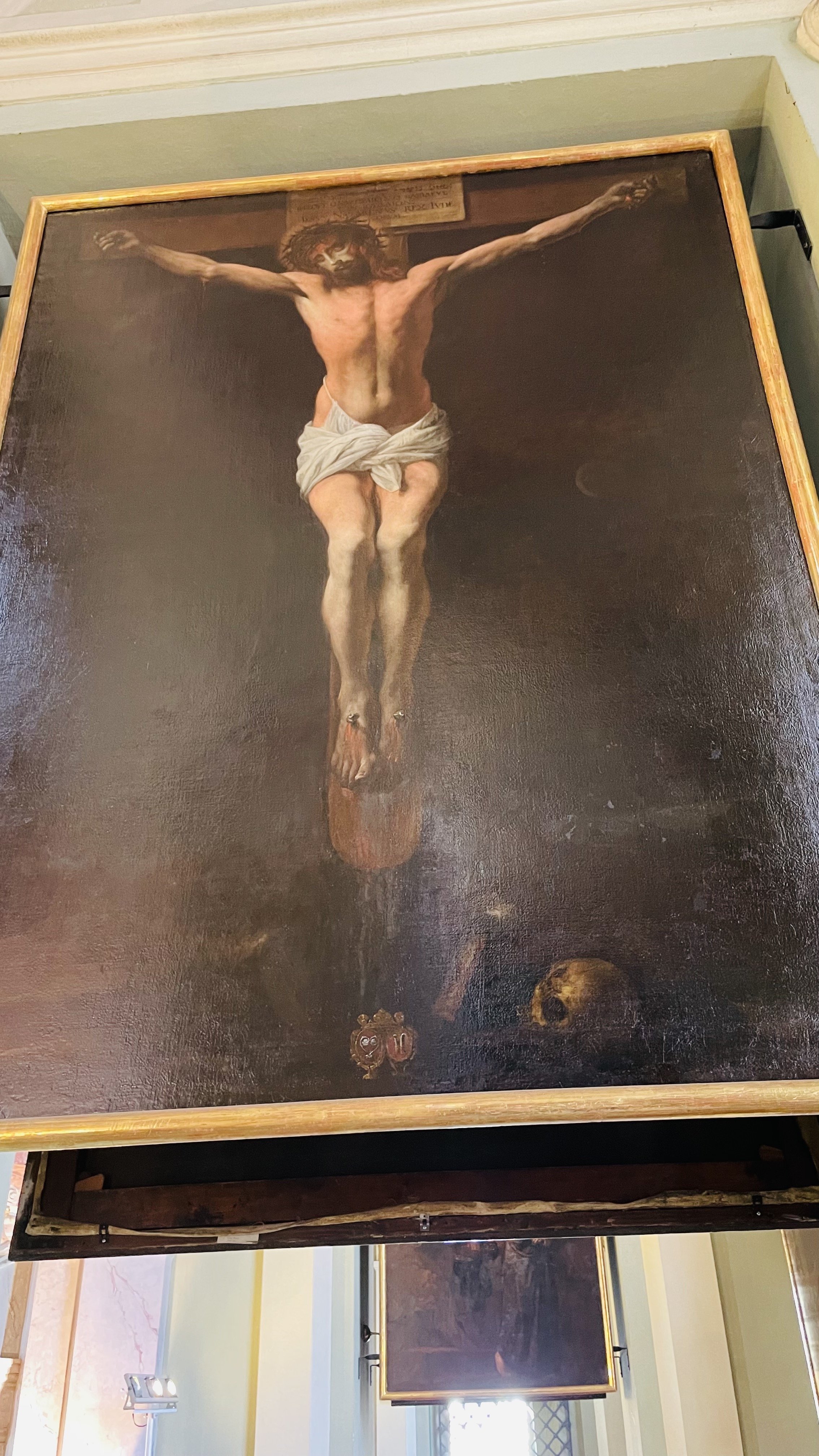

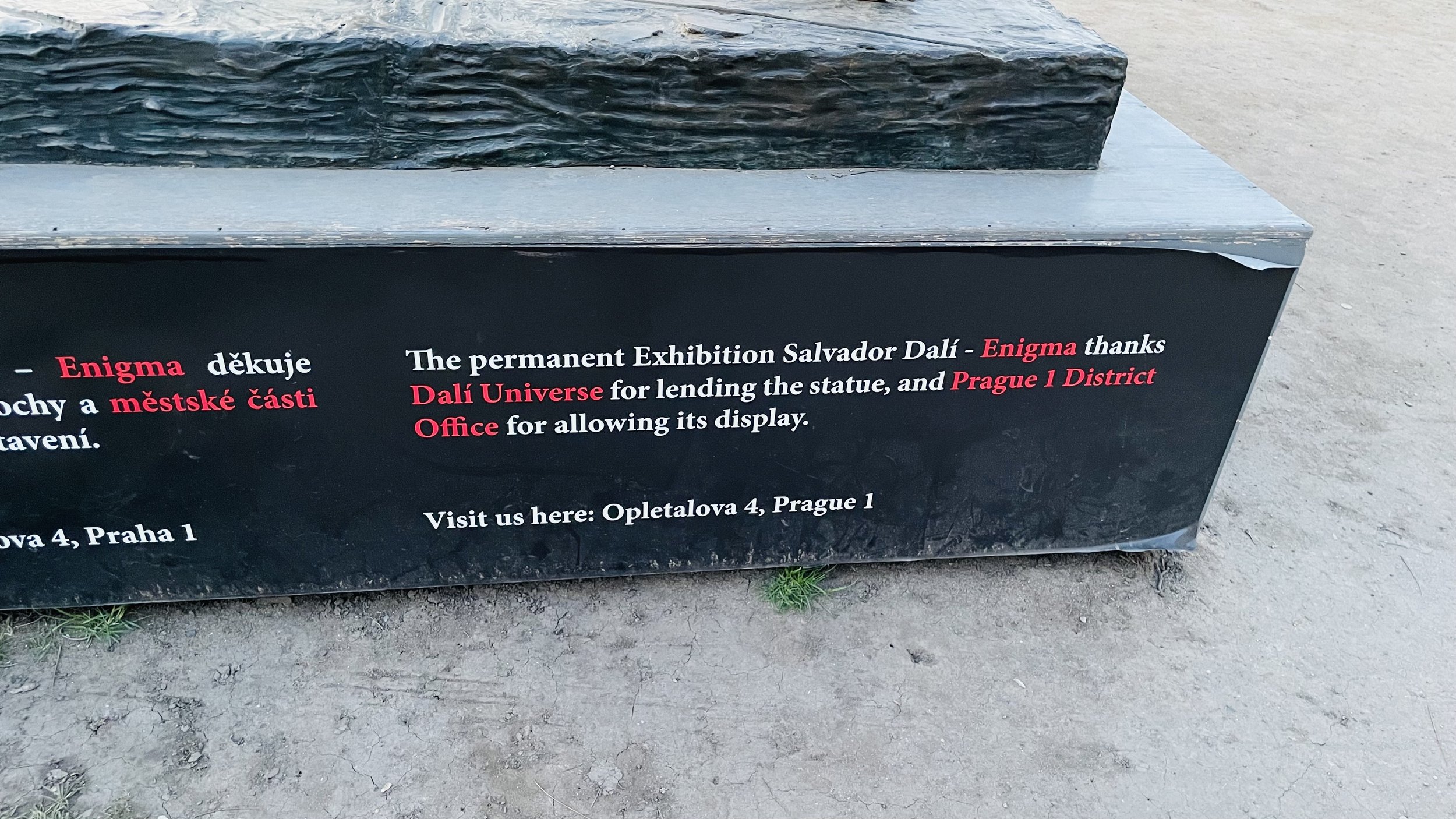

It is possible to witness a number of suggestive and loquacious palaces in the passage. Prague's edifices have a particularity: they can be read. The gaze rises and one can see numerous writings, many legible, others disguised. What messages do they spread? Then, there are coats of arms, logos, symbols, signs. And above all, countless statues. Praise characters, deities or simply artistic illusions. Prague's modern statues are also derived from the imagination.

David Černý is the new eccentric artist from Prague. He is like a Medieval sculptor. Saints have become satirical, ironic caricatures. He scattered Prague's centre and suburbs with unprecedented installations.

His plan is to overturn the statues, to provoke reading of the heroes, to confuse ordinary gestures like urinating in the river, to chop Kafka's head, to give legs to Trabant car.

It seems that he is climbing everywhere, but none of his works can be found in the Simulacrum of Prague: the Charles Bridge.

Praga, Prague, Charles Bridge

The splendid gothic Charles Bridge is a delight for statues, emblems, icons, saints, episodes of battles, captivity, devotion and prayer:

“Do you remember the green light of the street lamps on Charles Bridge? In this chimerical avenue, bordered by sandstone statues, in our times still passed lopsided carriages with rosy yellow lamps. Next to multitude of histrionic saints with a refined posture, the drunks sat on the stage of the bridge, clinging to the parapet, they talked to the river, with the stars reflected in the black water.” (5)

The original name was Stone Bridge. There was just a crucifix and a calvary. This bridge was renamed Charles Bridge in 1870. The Stone Bridge was a transit way between the banks, therefore, a meeting point. It was crossed by both gentlemen, novelists, painters, priests, professionals, artisans and beggars, bandits, thieves and vagabonds. Obviously, on the bridge stepped both authentic alchemists and charlatans.

In 1683, the Saint John of Nepomuk statue was erected where he was thrown from the bridge. It is made of bronze, the object of excruciating veneration. It is mystically touched by passers-by on the bridge until they corrode it.

Jan z Pomuku or Nepomucky was vicar of Prague and confessor to King Wenceslaus IV's wife. The king tried to extort his spouse's confidence from him but only obtained a stubborn refusal. Franco Cardini narrates his story in his book Prague Secret Capital of Europe:

“... the sovereign would have asked for the priest to reveal to him the details of the private behaviour of his wife, of whom he was the confessor. Having refused to break the sacrament, Father Jan was mercilessly tortured and finally, his body was tied to a millstone as ballast … thrown on 20 March 1383, from the Stone Bridge. But the Vltava is very deep at that point - between one and a half and two and a half metres - and full of currents: the body of the religious, blocked on the pebbly riverbed, was quickly recovered and became the object of a proud popular cult.” (6)

Statue of Bruncvík in Charlie Bridge

After the first statue was raised, a competition to build patron saints for arts and crafts began. The bridge filled up everywhere. There is even the Bruncvík Knight erected at the base of a pylon:

“And so, was born this admirable collection, a unique hard and engraved horizontal stone in the world, the heavy rump of its shoulders, transformed the bridge into a sort of majestic multi-headed centaur.” (7)

Whose statue will be next in Prague?

Jan Neruda, I racconti di Mala strana, Marietti 1820, Genova, VII ristampa, 2007, Pag. 211 Transled by the author

Jan Neruda, I racconti di Mala strana, Marietti 1820, Genova, VII ristampa, 2007, Pag. 55 Transled by the author

Jan Neruda, I racconti di Mala strana, Marietti 1820, Genova, VII ristampa, 2007, Pag. 21 Transled by the author

A cura di Harald Salfellner, Il Golem di Praga. Leggende ebraiche dal ghetto, Accademia Vis Vitalis, 2014, Pag. 45 Transled by the author

Angelo Maria Ripellino, Praga magica, Einaudi, Torino, I edizione Saggi, 1973, Pag. 244 Transled by the author

Franco Cardini, Praga Capitale segreta d'Europa, ilMulino, Bologna, 2020, Pag. 45 Transled by the author

Angelo Maria Ripellino, Praga magica, Einaudi, Torino, I edizione Saggi, 1973, Pag. 248 Transled by the author

Bibliography:

Jan Neruda, I racconti di Mala strana, Marietti 1820, Genova, VII ristampa, 2007

A cura di Harald Salfellner, Il Golem di Praga. Leggende ebraiche dal ghetto, Accademia Vis Vitalis, 2014

Angelo Maria Ripellino, Praga magica, Einaudi, Torino, I edizione Saggi, 1973

Franco Cardini, Praga Capitale segreta d'Europa, ilMulino, Bologna, 2020

Mauro Boselli, Luca Rossi, Nicola Genzianella, I misteri di Praga, Sergio Bonelli editore, Milano, 2016

Praga e la Repubblica Ceca, Lonely Planet, 10° edizione italiana, marzo 2013

Koh Samui is paradise.

It is a green area with hills and picturesque beaches.

It is a youthful oasis, with many young people from all over the world. They have fun on the sand during the day. In the evening, they drink and dance at the Ark Bar on Chaweng Beach.

In Prague, only the imagination remained. It is a city to imagine. Let's imagine Prague during the Medieval era, imagine the dark streets, imagine the cold winter, imagine the mist, imagine the empty alleys, imagine the strange noises in the silence, imagine this gloomy atmosphere combined with the traditions of own religion.

Turin and Egypt

Baku between East and West like the love of Ali and Nino

Lugano, Ceresio Lake and Luigi Pirandello

Also, on 13 June but in 1888, Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa was born in Lisbon. He is simply known as Fernando Pessoa, although in his life he had many literary names. In Pessoa, there is a clear reference to Saint Anthony: Fernando and Antonio. He is the mark of his future Catholic dedication and of an alleged genealogical descend on the Saint.

Venice is expressive, dreamlike, mysterious. Any place has an anecdote. Any place has a past, not necessarily important. There is also a private narration made up of many people capable of building the charm of the city.

https://www.facebook.com/roberto.matteucci.7

http://linkedin.com/in/roberto-matteucci-250a1560

“There’d he even less chance in a next life,” she smiled.

“In the old days, people woke up at dawn to cook food to give to monks. That’s why they had good meals to eat. But people these days just buy ready-to-eat food in plastic bags for the monks. As the result, we may have to eat meals from plastic bags for the next several lives.”

Letter from a Blind Old Man, Prabhassorn Sevikul (Nilubol Publishing House, 2009)

Budapest is the city of Sándor Márai. He was born in Košice, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, and committed suicide in San Diego, USA. Yet, Sándor Márai is inextricably linked to Budapest: the city of his education, of the tragedies of the Second World War, of the Nazi occupation and the liberation by the Red Army.