The Portrait of the Artist. In the Mirror of Narcissus. The Face, the Mask, the Selfie Forlì, Museo Civico San Domenico

Nello specchio di Narciso. Il ritratto dell'artista. Il volto, la maschera, il selfie

The Portrait of the Artist. In the Mirror of Narcissus. The Face, the Mask, the Selfie

Forlì, Museo Civico San Domenico

Piazza Guido da Montefeltro

From 23 February to 29 June 2025

Curated by Cristina Acidini, Fernando Mazzocca, Francesco Parisi, and Paola Refice

Author: Roberto Matteucci

Click Here for Italian Version

Is narcissism a primary quality for an artist?

Without narcissism, could an artist experience aesthetic and poetic stimuli?

According to the elegant exhibition The Portrait of the Artist. In the Mirror of Narcissus. The Face, the Mask, the Selfie - curated by Cristina Acidini, Fernando Mazzocca, Francesco Parisi, and Paola Refice at the Museo Civico San Domenico in Forlì - the answer is definitive: narcissism is an undeniably and irrefutably inspiring genius.

The artist must be a narcissist—in character, in nature, in aesthetic madness and insanity, in egoism, and in artistic transgression with

"... sexual and egoistic instinctual forces not merely accidentally participate in the creation of the artwork, but actually decisively determine its development and structure ..." (1).

Thus Otto Rank, a disciple of Sigmund Freud, describes the use of psychology and psychoanalysis in art in his book The Incest Theme in Literature and Legend: Fundamentals of a Psychology of Literary Creation. Although departing from the theme of incest, the same principle can also apply to narcissism.

This is the message of the Forlì exhibition: to read, in the self-portrait, the vainglory of painters and sculptors, the hidden latent symbols of their creations.

Narcissus discovers his own gorgeousness in the water of

“There was an unclouded fountain, with silver-bright water ...” (2),

simply by prostrating himself on the ground:

“While he drinks he is seized by the vision of his reflected form. He loves a bodiless dream. He thinks that a body, that is only a shadow. He is astonished by himself, and hangs there motionless, with a fixed expression, like a statue carved from Parian marble.” (3)

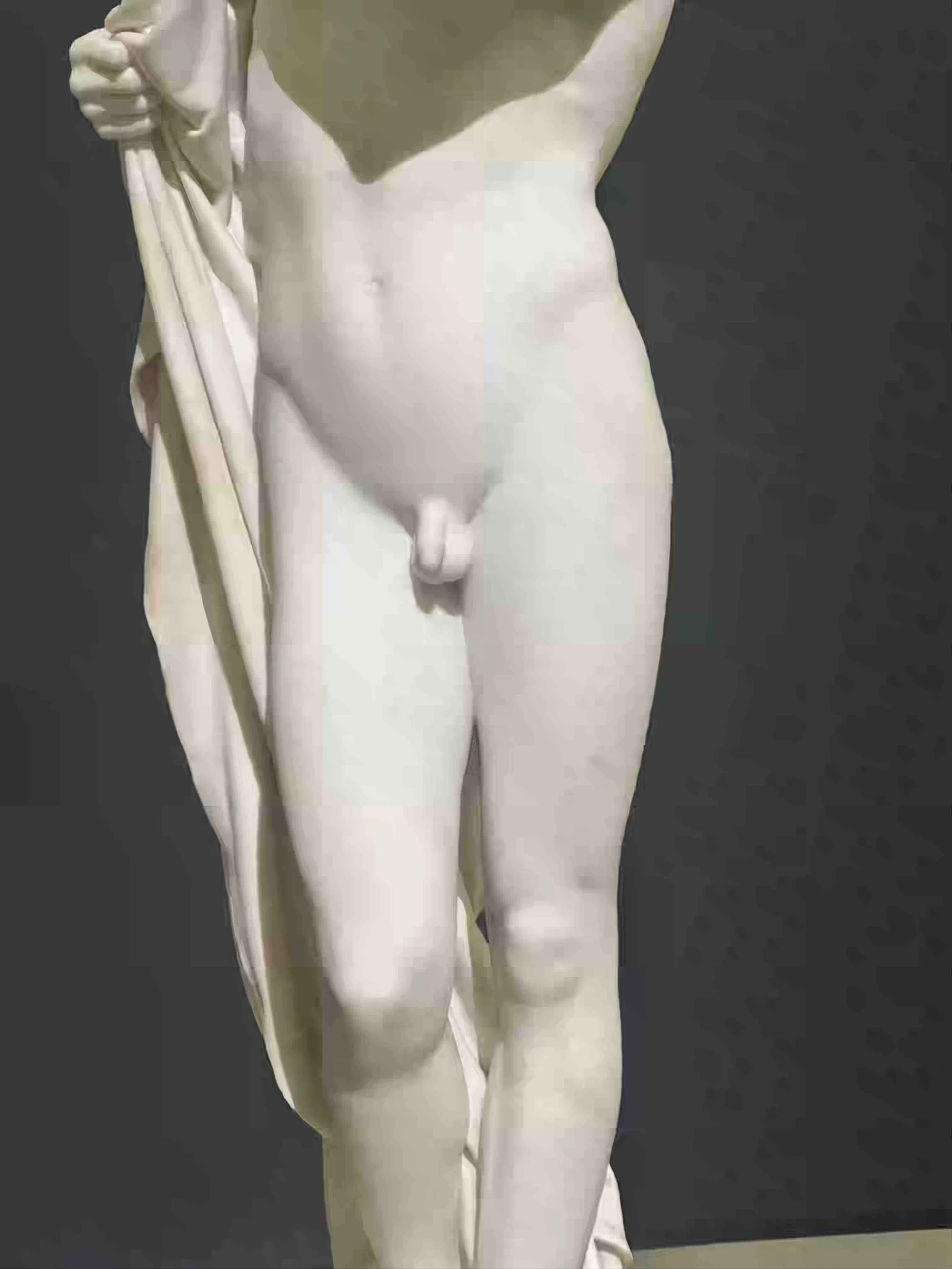

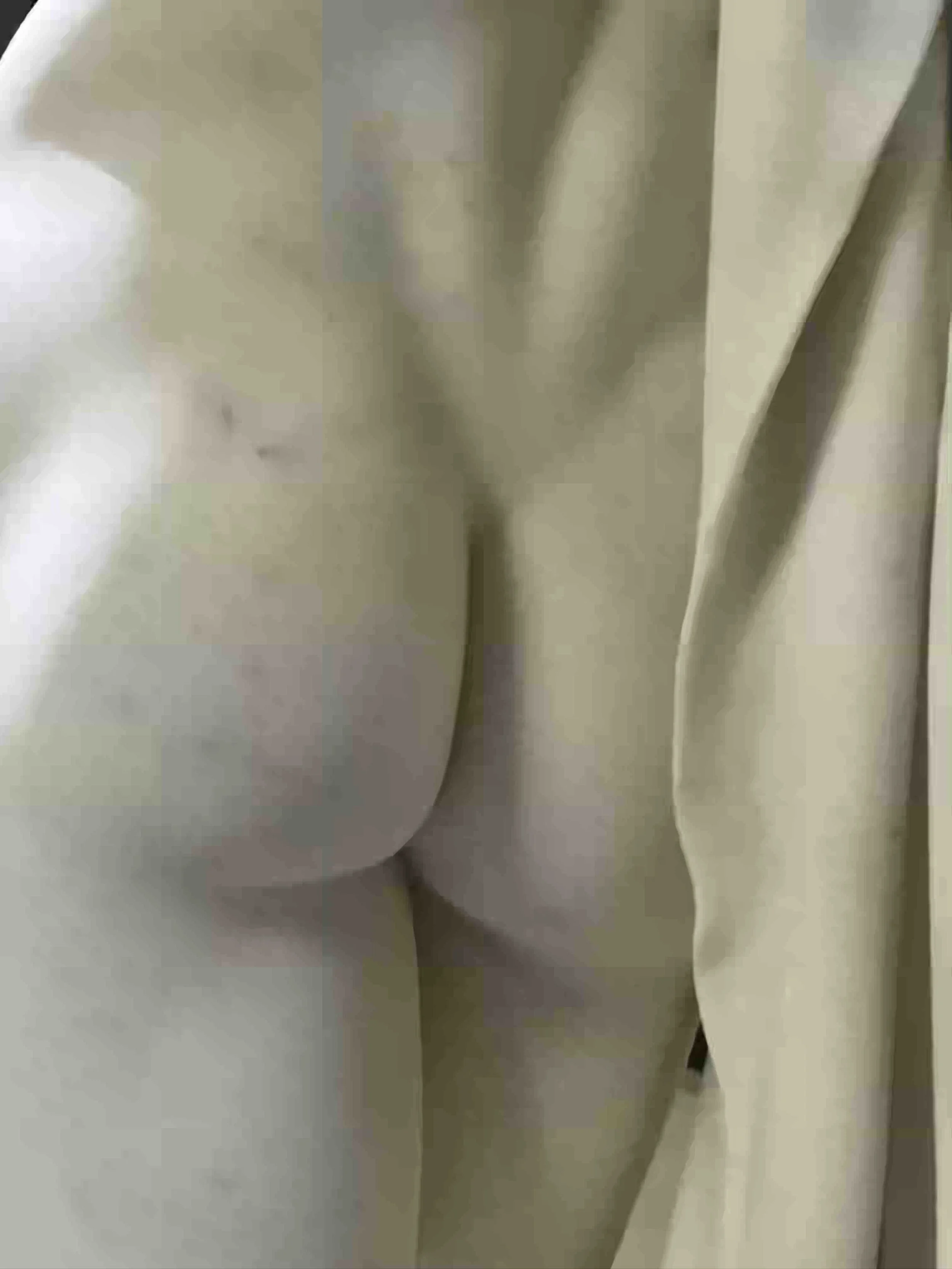

Narcissus remains enraptured, entranced, like the sculptor Pygmalion, who speaks, embraces, and kisses his perfectly crafted statue:

“... not admitting it to be ivory. He kisses it and thinks his kisses are returned; and speaks to it; and holds it, and imagines that his fingers press into the limbs, and is afraid lest bruises appear from the pressure. Now he addresses it with compliments, now brings it gifts that please girls …” (4)

Both Narcissus and Pygmalion love a superlative artwork. Both have created one. Narcissus, simply, by mirroring in the spring, Pygmalion with his chisel. Both adore their creations as they adore themselves, to the point of paradox.

The same paradox gave rise to the legend of Michelangelo, who, astonished, wondered why his David did not speak. It is a legend. However, years later, in 1913, Sigmund Freud would animate and give personality, through psychoanalysis, to another of Michelangelo's majestic sculptures, The Moses in the Basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli:

“Perhaps the right hand was gripping the beard with greater force, had reached the left edge of the beard, and when it withdrew into the position we see in the statue today, a part of the beard followed it and now remains to witness the movement that had just occurred.” (5)

Narcissus did not require manual labour, but normally and spontaneously made a gesture. Despite this simplicity, he engendered the most harmonious of masterpieces. Harmonious because it was himself. Others had to draw on genius and hard work.

The artist is a narcissist, therefore he loves himself and loves his creation to the point of animating it.

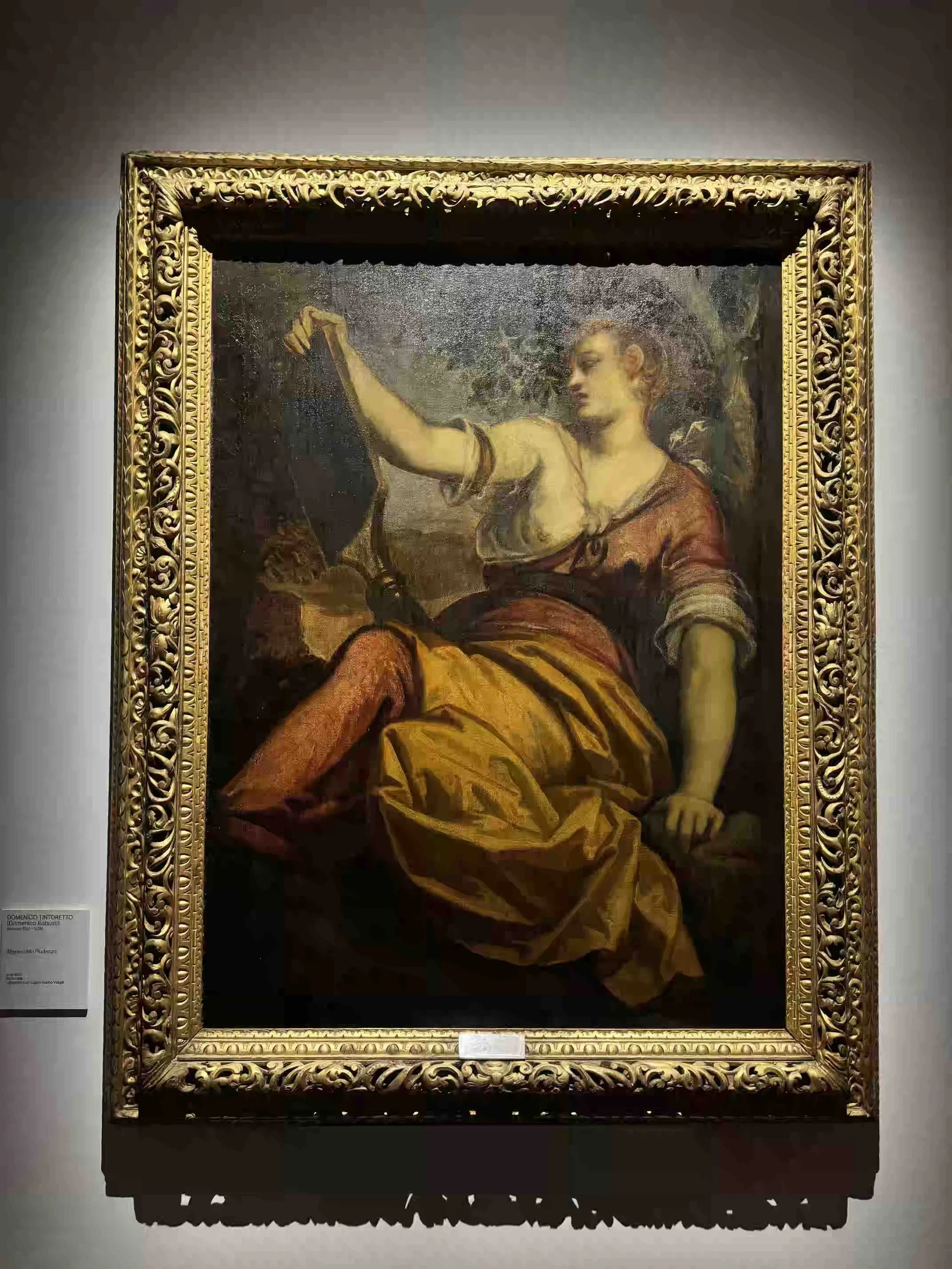

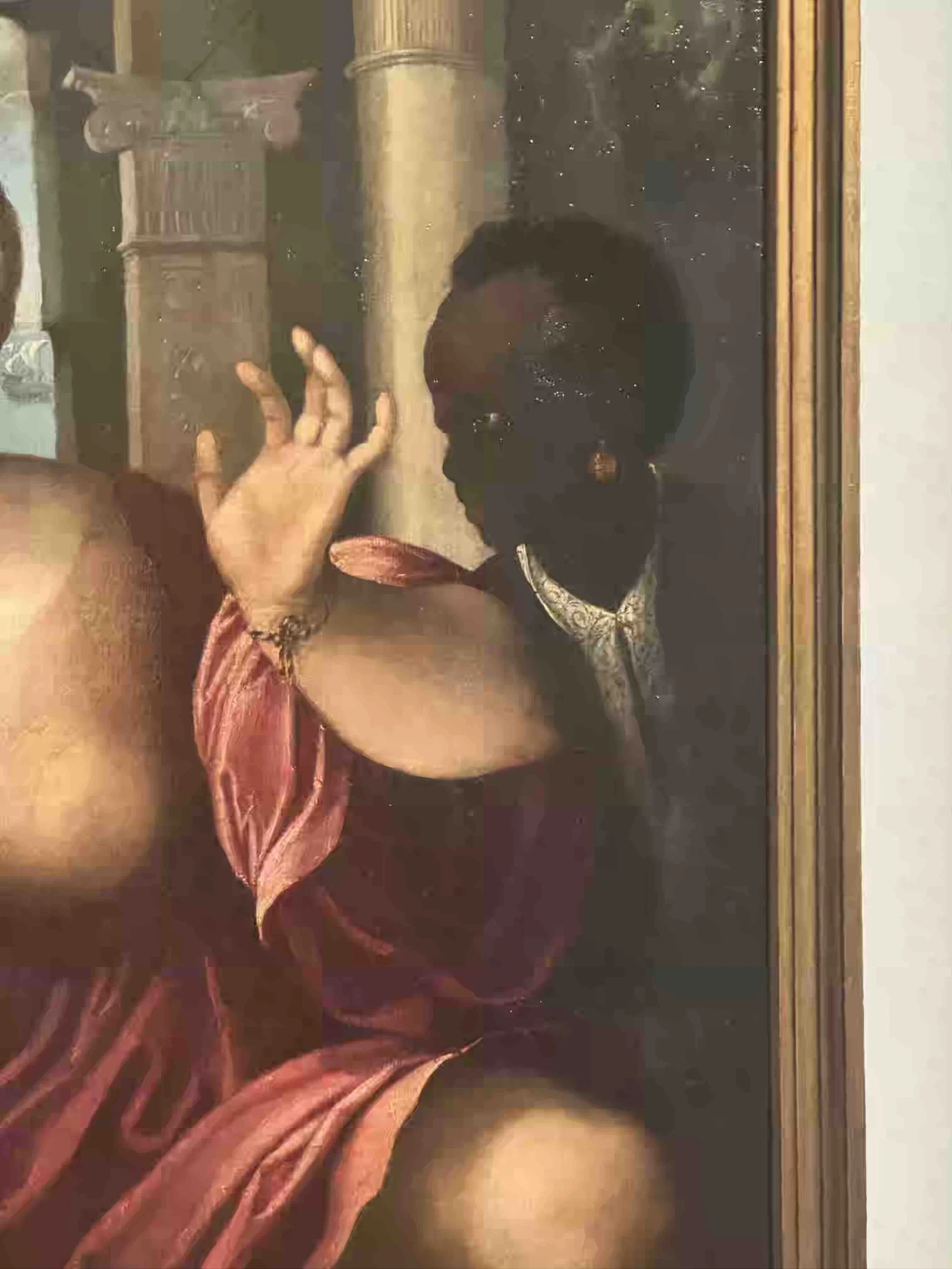

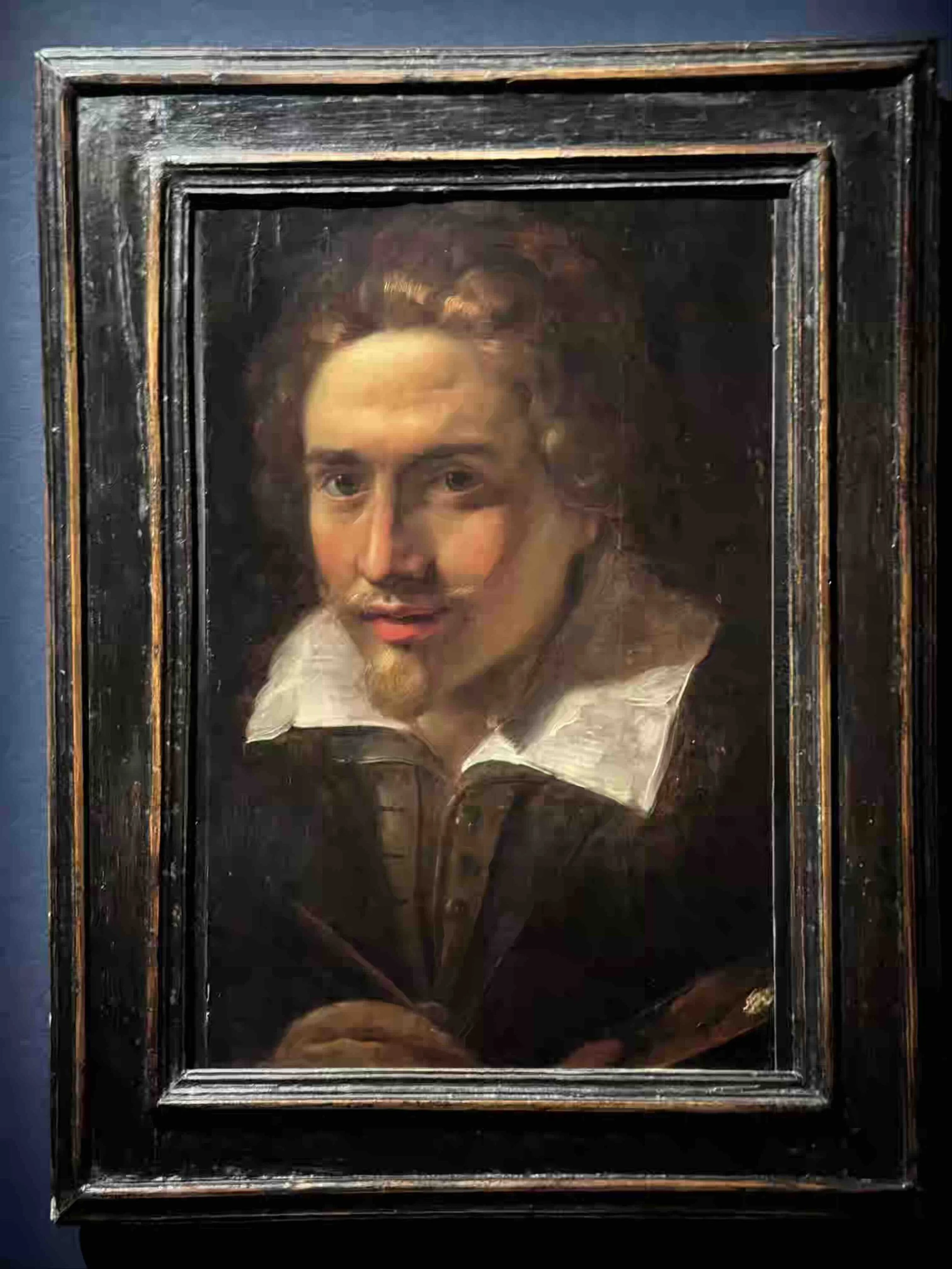

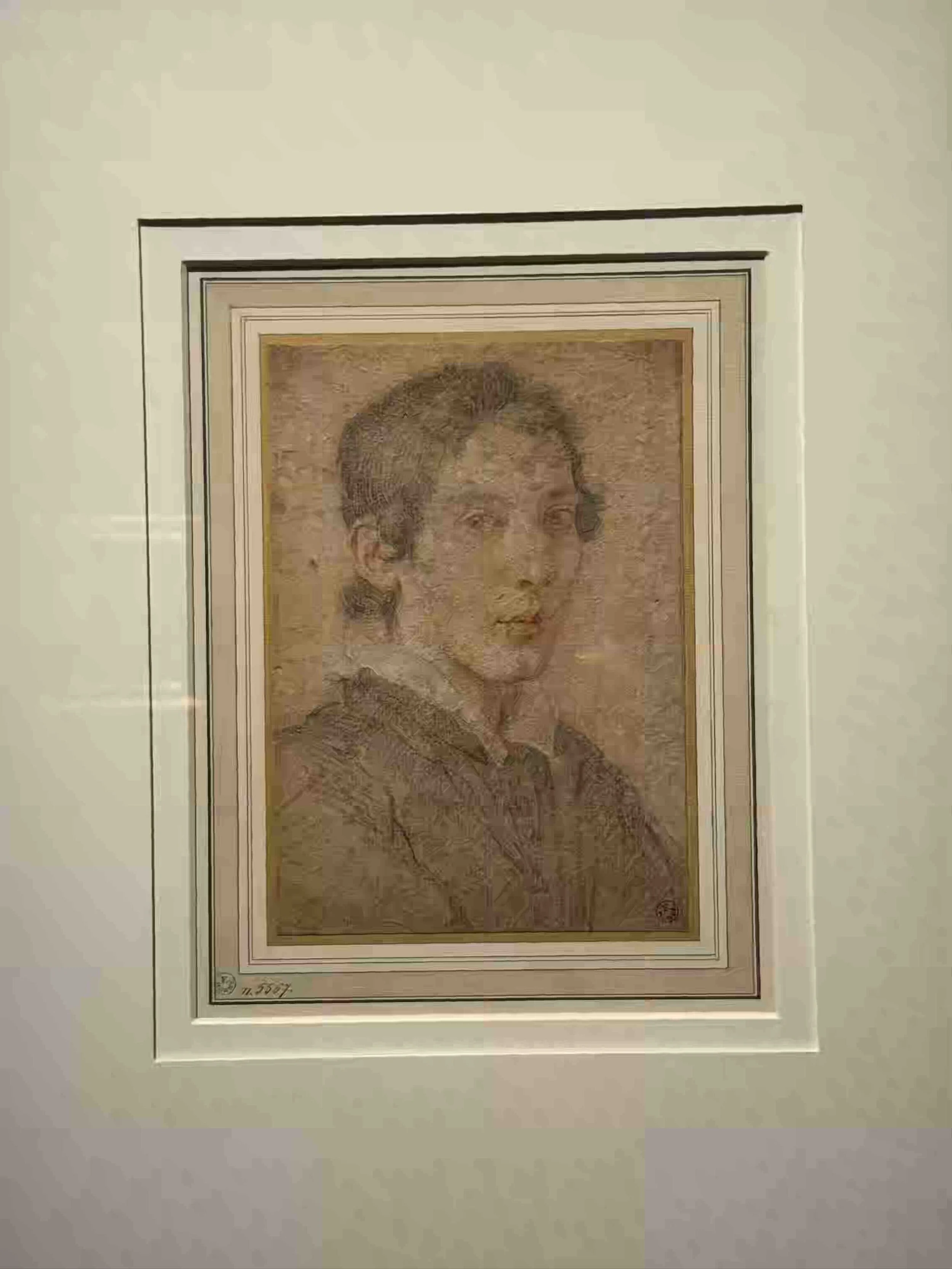

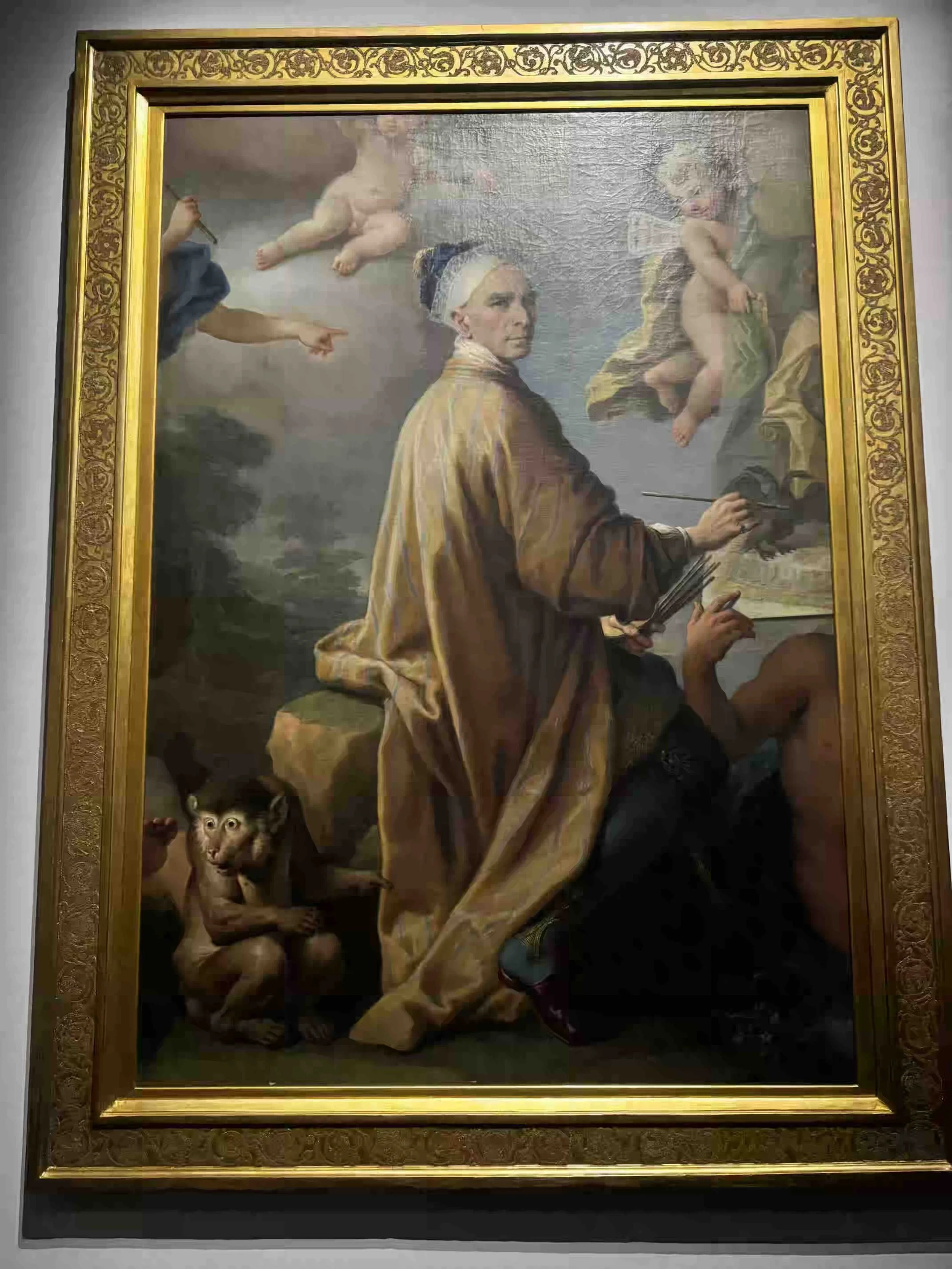

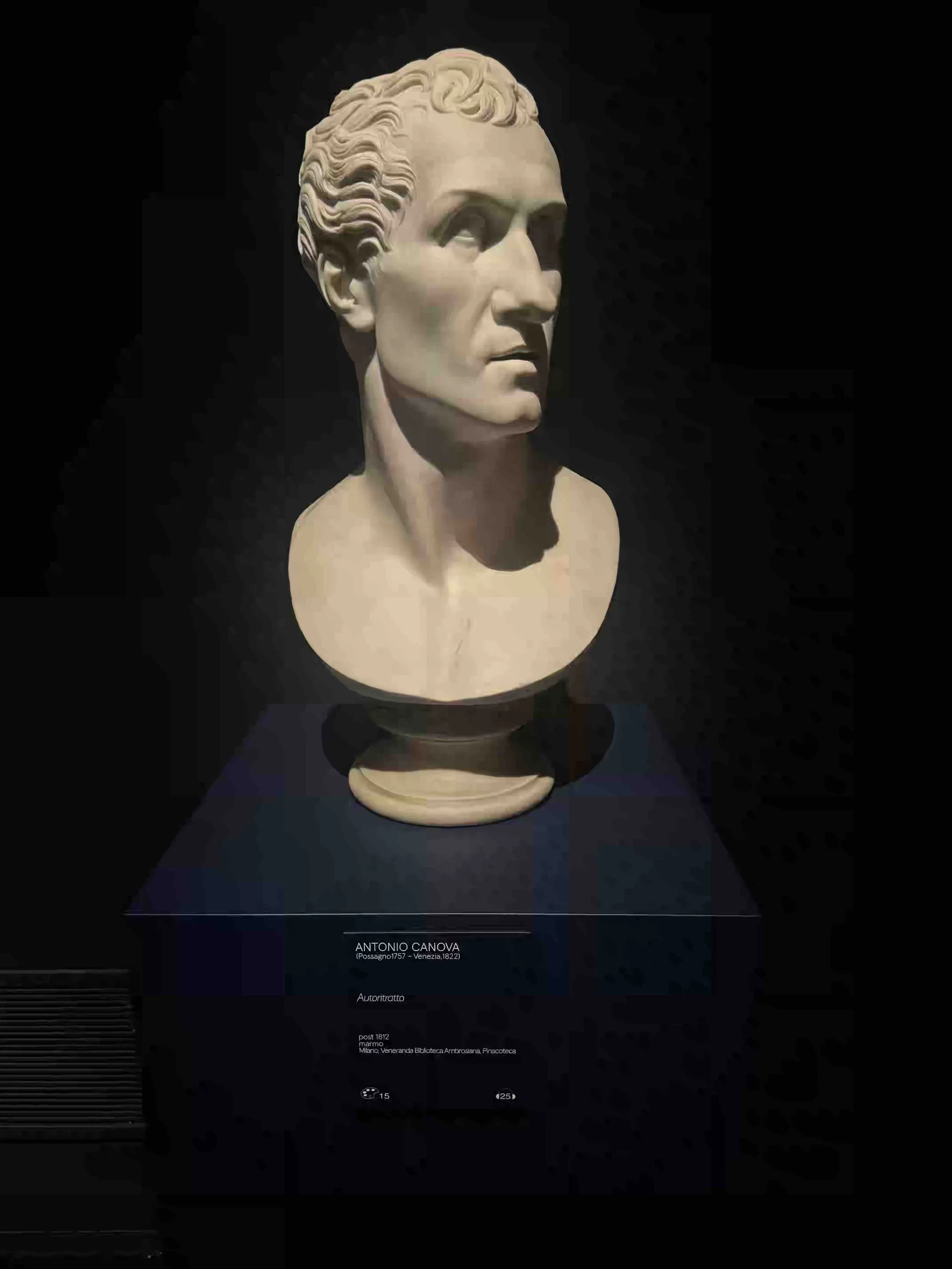

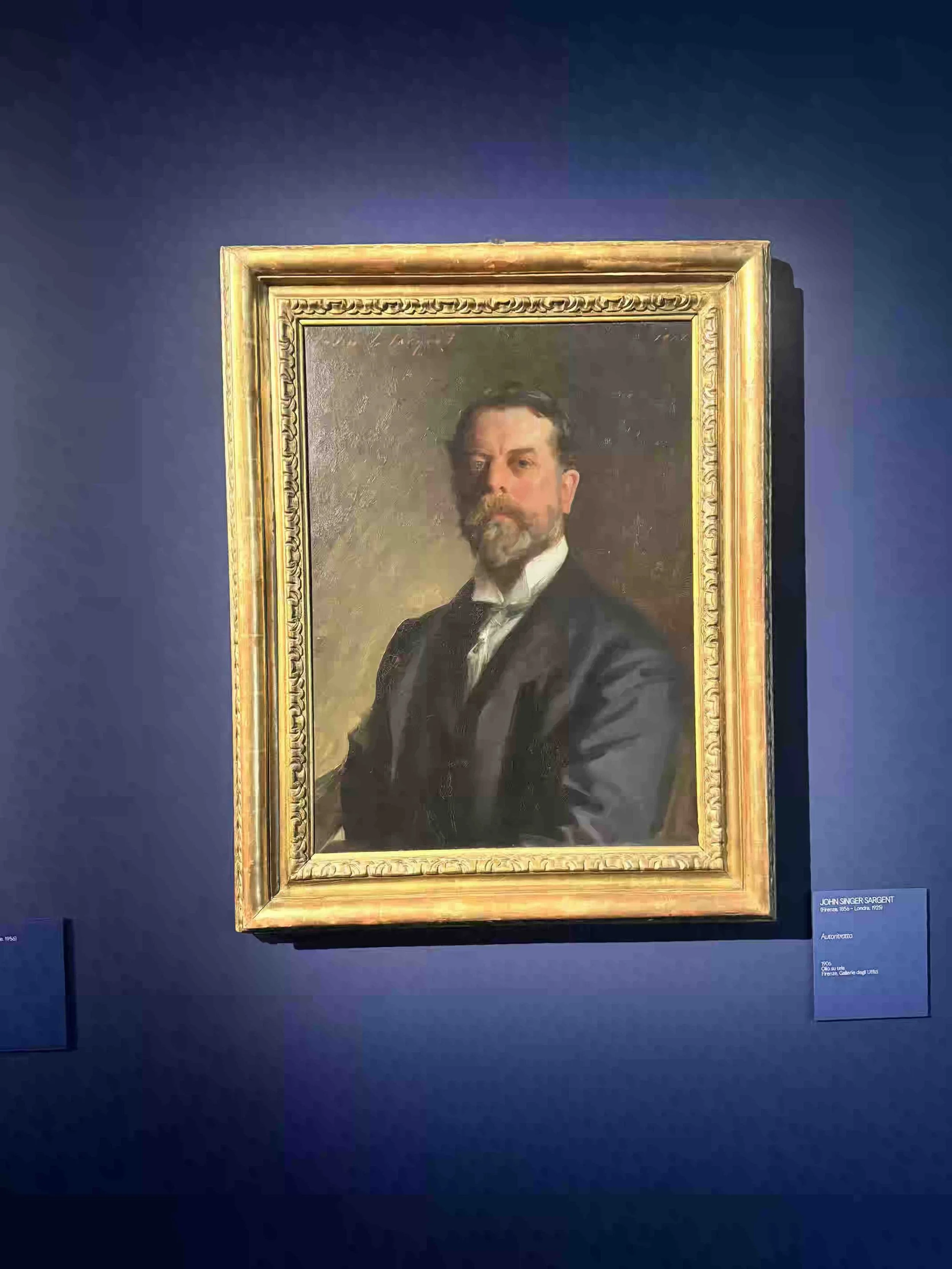

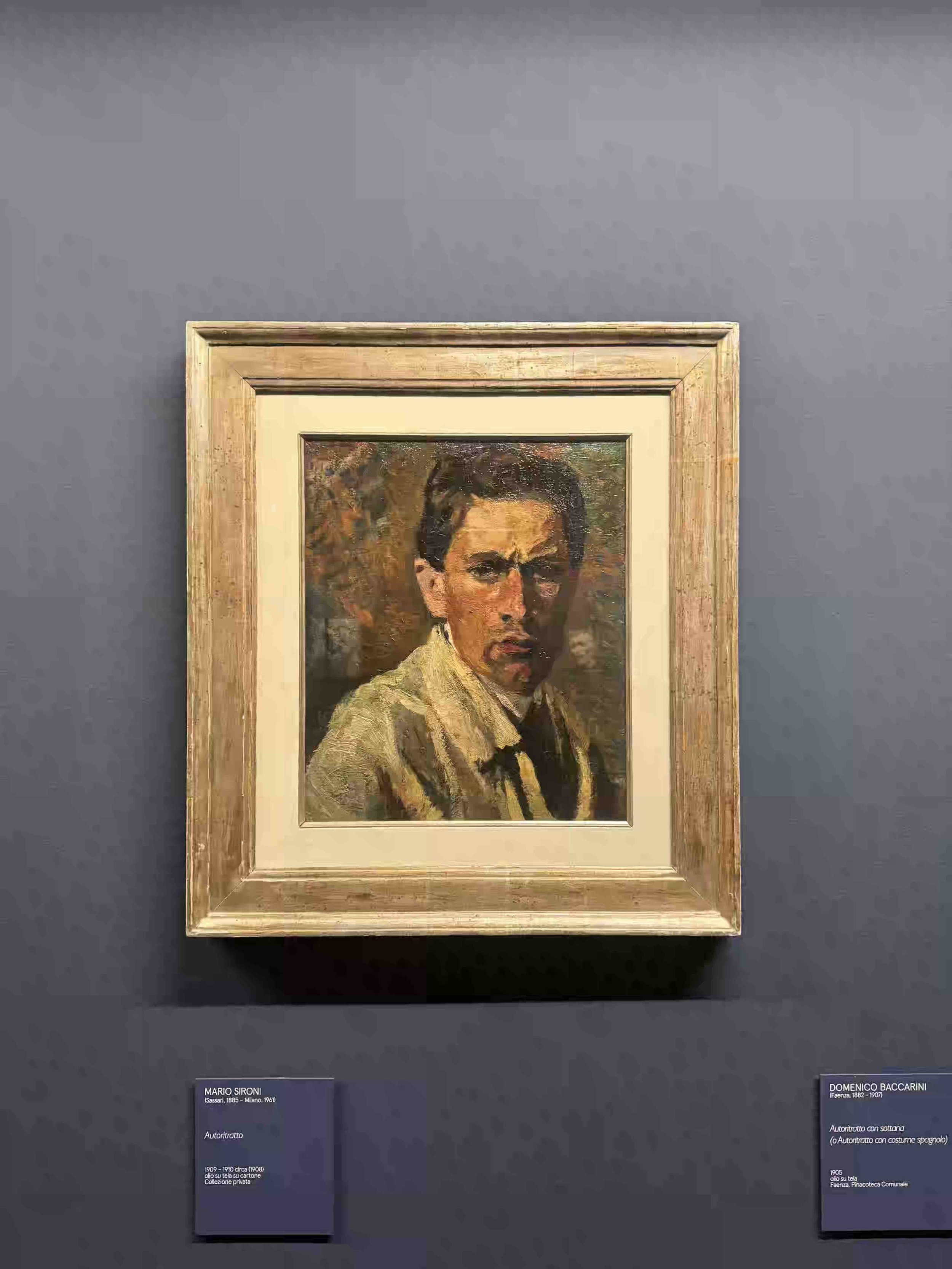

With more elegant and refined actions, many artists could not resist the temptation to portray themselves as the most splendid representations in their artworks. Some of the finest self-portraits on display in the exposition are by Bellini, Tintoretto, Titian, Lotto, Bernini, Pontormo, Artemisia Gentileschi, Giordano, Annigoni, Hayez, Rubens, Canova, Sironi, Balla, Pistoletto, and Bill Viola.

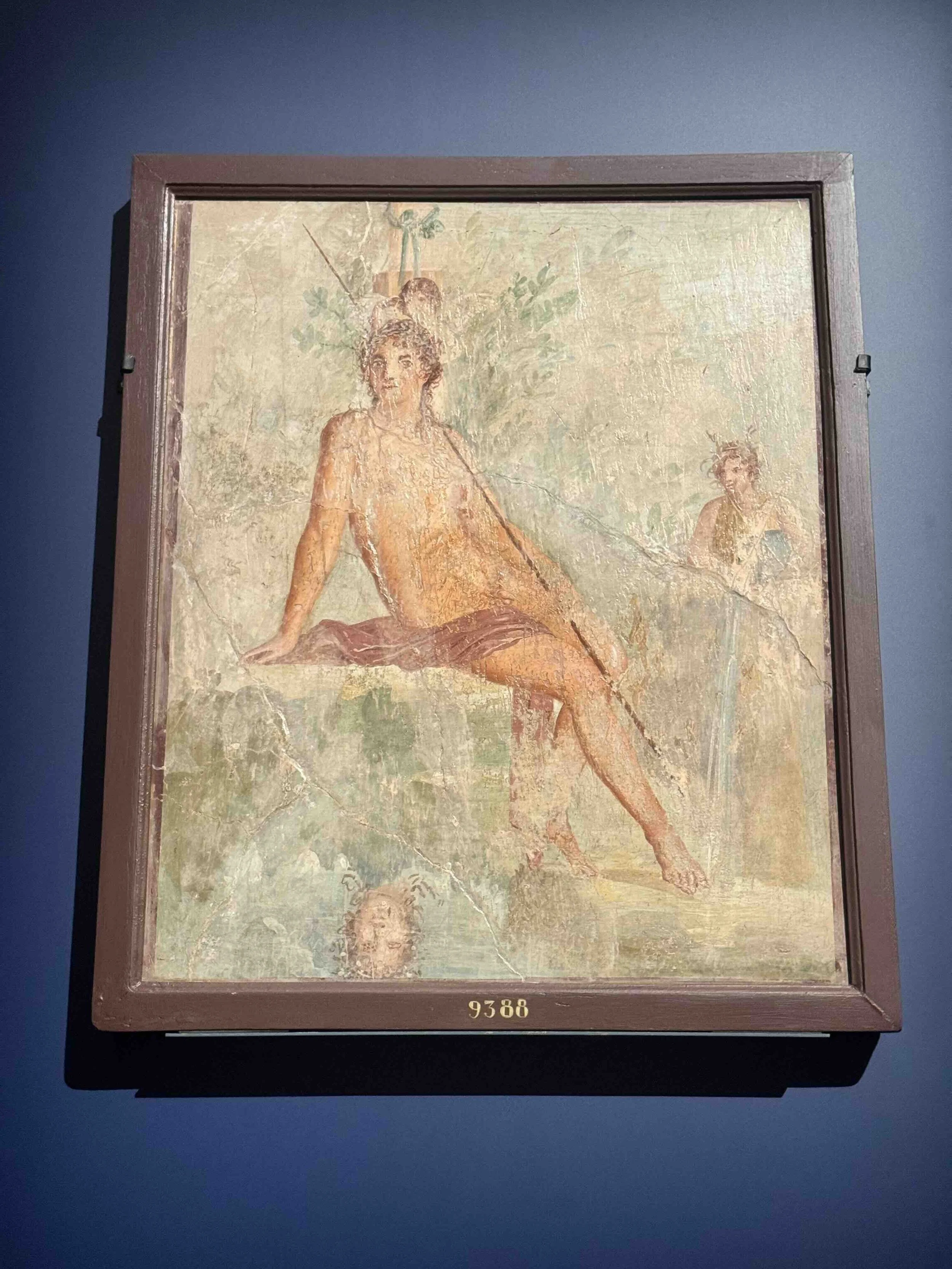

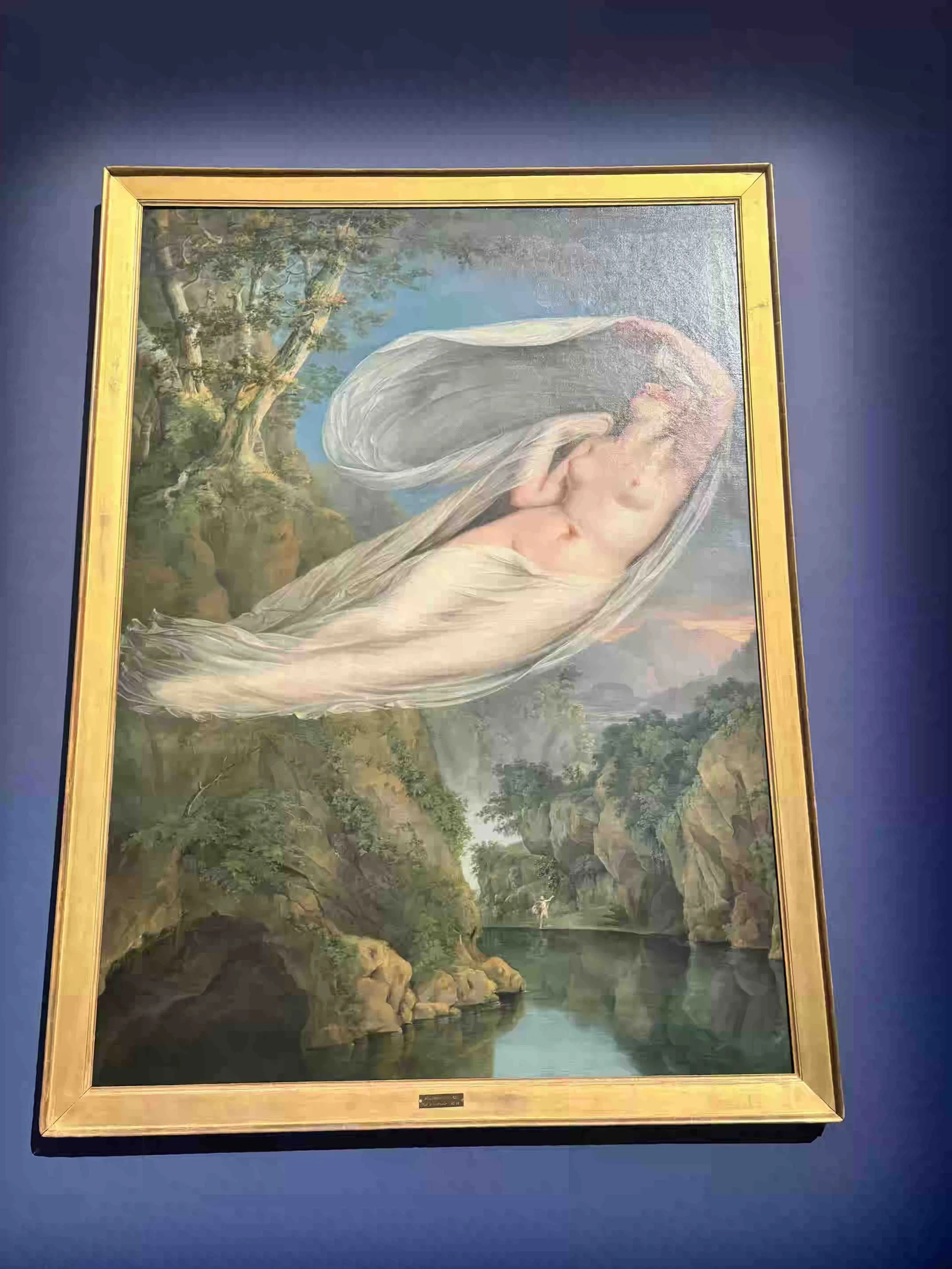

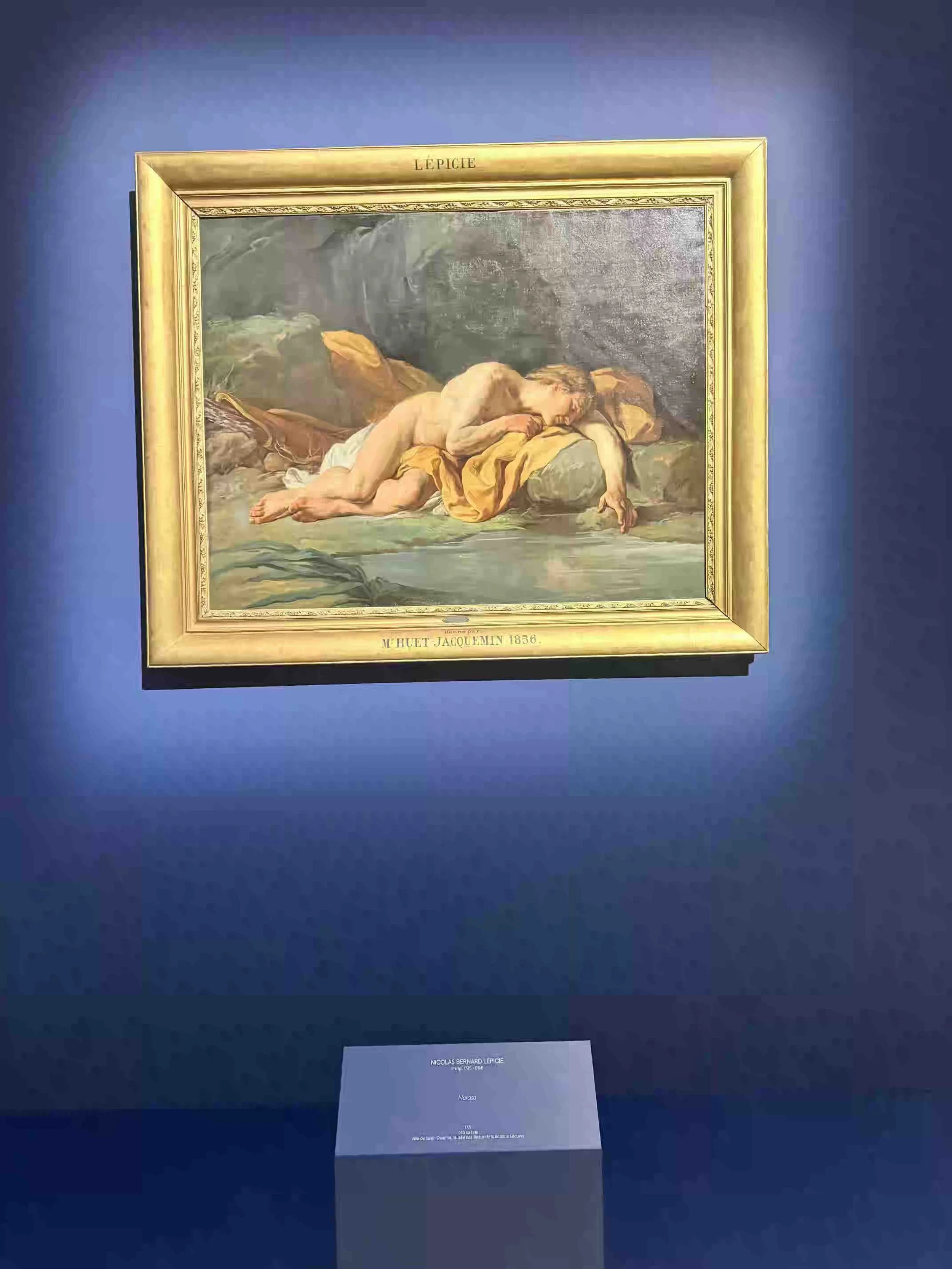

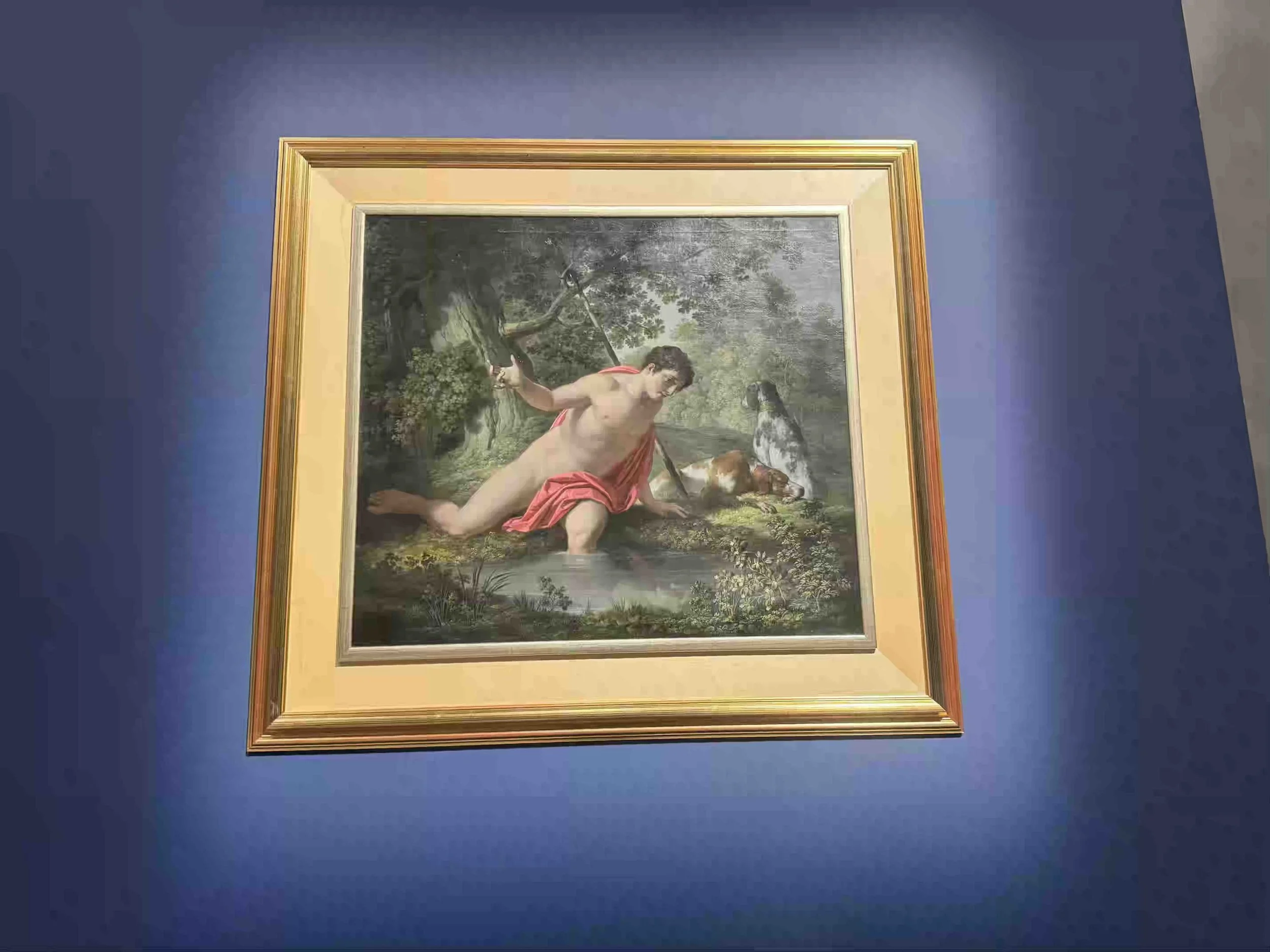

The exhibition begins with many figures of Narcissus, each exploiting the only means of revealing their physical specificity at the time: a pool of water.

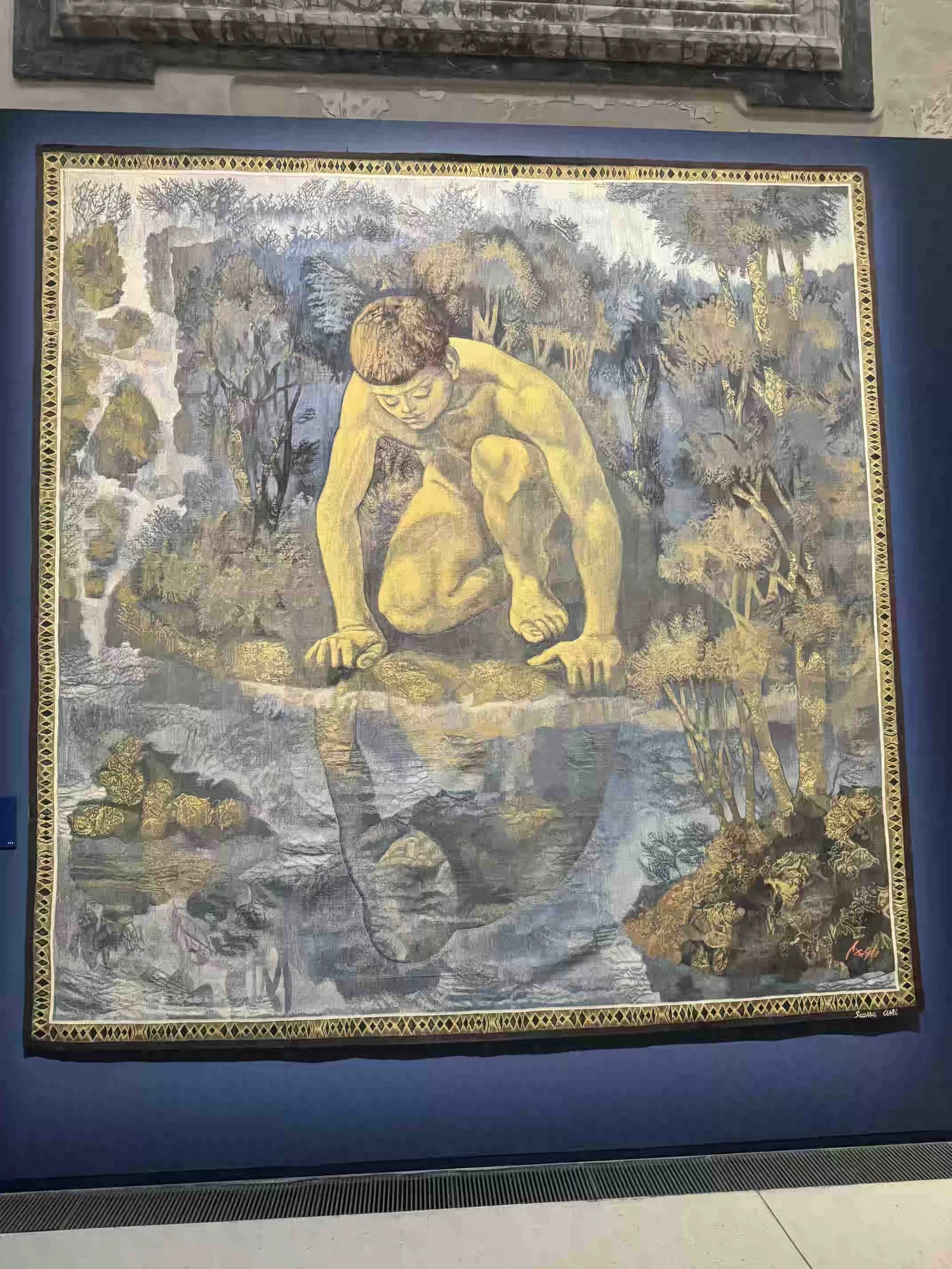

Corrado Cagli, Narciso

In this section, Corrado Cagli's tapestry, Narciso (Narcissus), depicts a young nude, with a sculptural and vigorous carnality, with enormous hands, arms, and feet. His gaze is fixed on the water. His form is reflected in shades of blue. All around is a luxuriant nature. On the right, a stream reinforces his duality. The journalist Lauretta Colonnelli, with culture and intelligence, recognizes in Cagli's Narciso the

"… Pasolinian street youths and their poignant tenderness." (6)

With the introduction of the glass mirror, beauty is reflected in the soul, with vanity controlling all the truths of life.

Francesco Rustici detto il Rustichino, Allegoria della Prudenza e della Sapienza

Rustichino, Allegoria della Prudenza e della Sapienza

In the Allegoria della Prudenza e della Sapienza (Allegory of Prudence and Wisdom) by Francesco Rustici, known as Rustichino, there are two women. One is depicted in profile, reflected in a large mirror, held in her hand, from which emerge her imposing pointed nose, thin lips, a big and cheerful eye, beautiful red cheeks. On her long neck is a pendant. Does the reflected image coincide with the lady's real beauty, or is it merely a dreamed vanity?

With the self-portrait, the artwork belongs entirely to its author, both as a production and as a subject. The artist becomes an integral part of the context, standing alongside the other figures, as Raphael does in The School of Athens. He observes, with the self-assured satisfaction of one fully conscious of his success, the line of enthusiastic spectators before his masterpiece:

“In the fifteenth century, for the first time, artists felt the need to represent themselves by including their own portraits in group scenes. They appear as commentators on the moral significance of the artwork or as witnesses ...” (7)

Francesco Hayez, Autoritratto con tigre e leone

Another category of self-portraits is the interior, introspective, almost spiritual one:

“It is the single portrait, frontal or three-quarter view, conceived to achieve depth. The eyes, which now appear turned toward the interlocutor, were actually intent on peering into the mirror while the painter copied his own reflected face.” (7)

In Autoritratto con tigre e leone (Self-Portrait with Tiger and Lion), Francesco Hayez portrays himself with two noble beasts, a lion and a tiger, locked in a cage in a circus in Milan. Hayez is in mid-shot, three-quarter, scrutinizing the visitor. He is dressed totally in black, indifferent to the animals behind the bars. Hayez occupies a small segment of the right corner. The true protagonists are the great felines. The lion lies peacefully, stretched out in indolent calm. The tiger moves languidly, looking placidly at Hayez. It is an interpretation of a distinctive world. Outside Milan, Hayez's city, there are different realities as diverse as the predators in the cage. They are unusual environments, yet impressive and fascinating. Hayez is aware, therefore he steps aside, leaving the focus to the beasts.

The artist's temperament is complex and intuitive. Understanding it necessitates passion, study, and research. It is an analysis of creative force and energy, of the liberation of the artist and the viewer. In the self-portrait, the Aristotelian catharsis occurs not in the spectator but in the artist:

“Given the same natural qualifications, he who feels the emotions to be described will be the most convincing; distress and anger, for instance, are portrayed most truthfully by one who is feeling them at the moment.” (8)

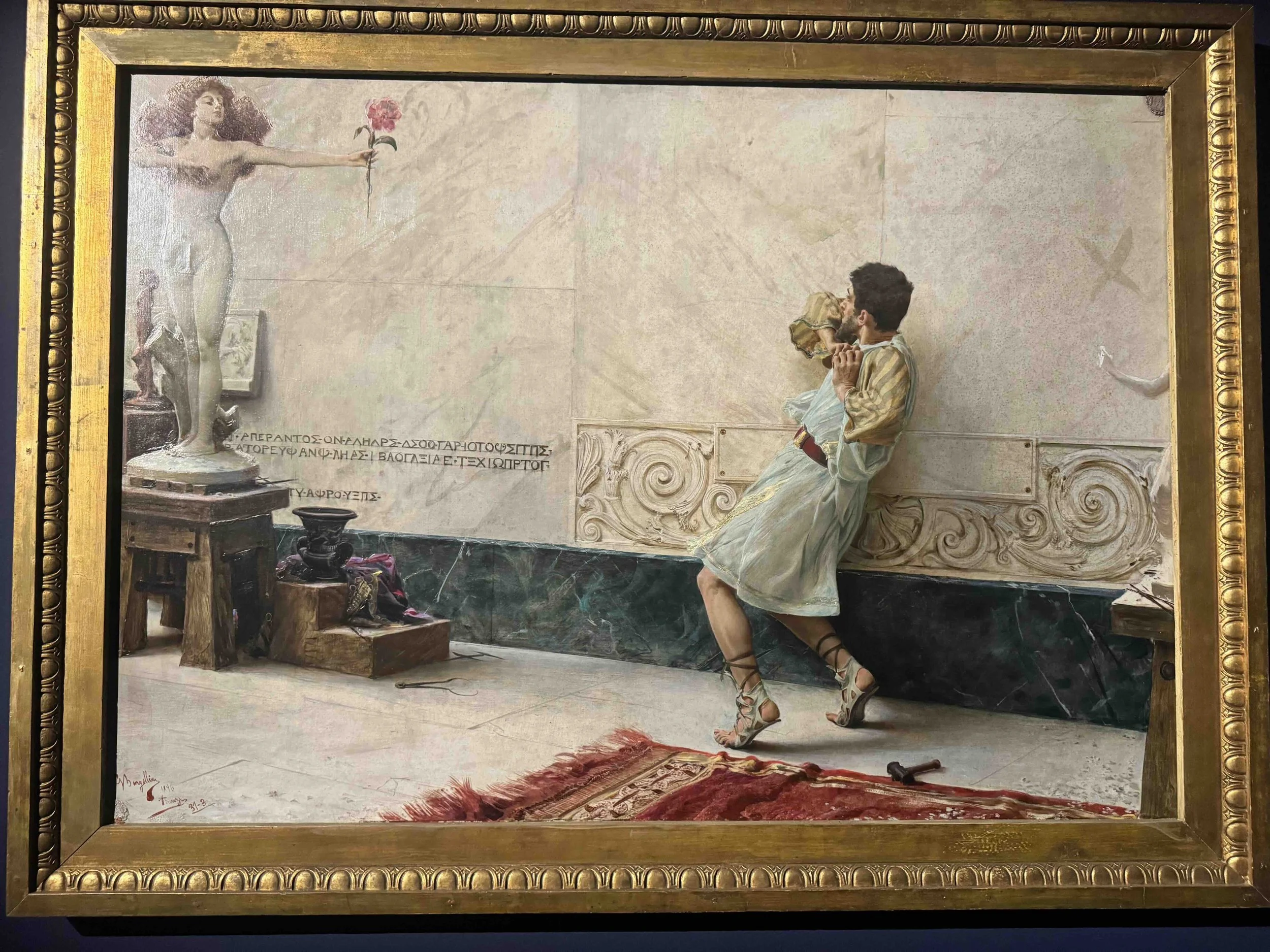

In the exhibition, Pygmalion is represented in Giulio Bargellini's version. Pygmalion is intimidated rather than enamored by his statue, which dominates from its pedestal. She has a flower in her hand. Long, flowing hair covers her head. The body has an aristocratic refinement, the left arm stretched out threateningly and resolutely, as if issuing a command. The right arm casually hides her breast. Behind Pygmalion, on the ground, lies his chisel, abandoned after discovering his marvellous sculpture. He is no longer a sculptor, but simply a man infatuated with beauty.

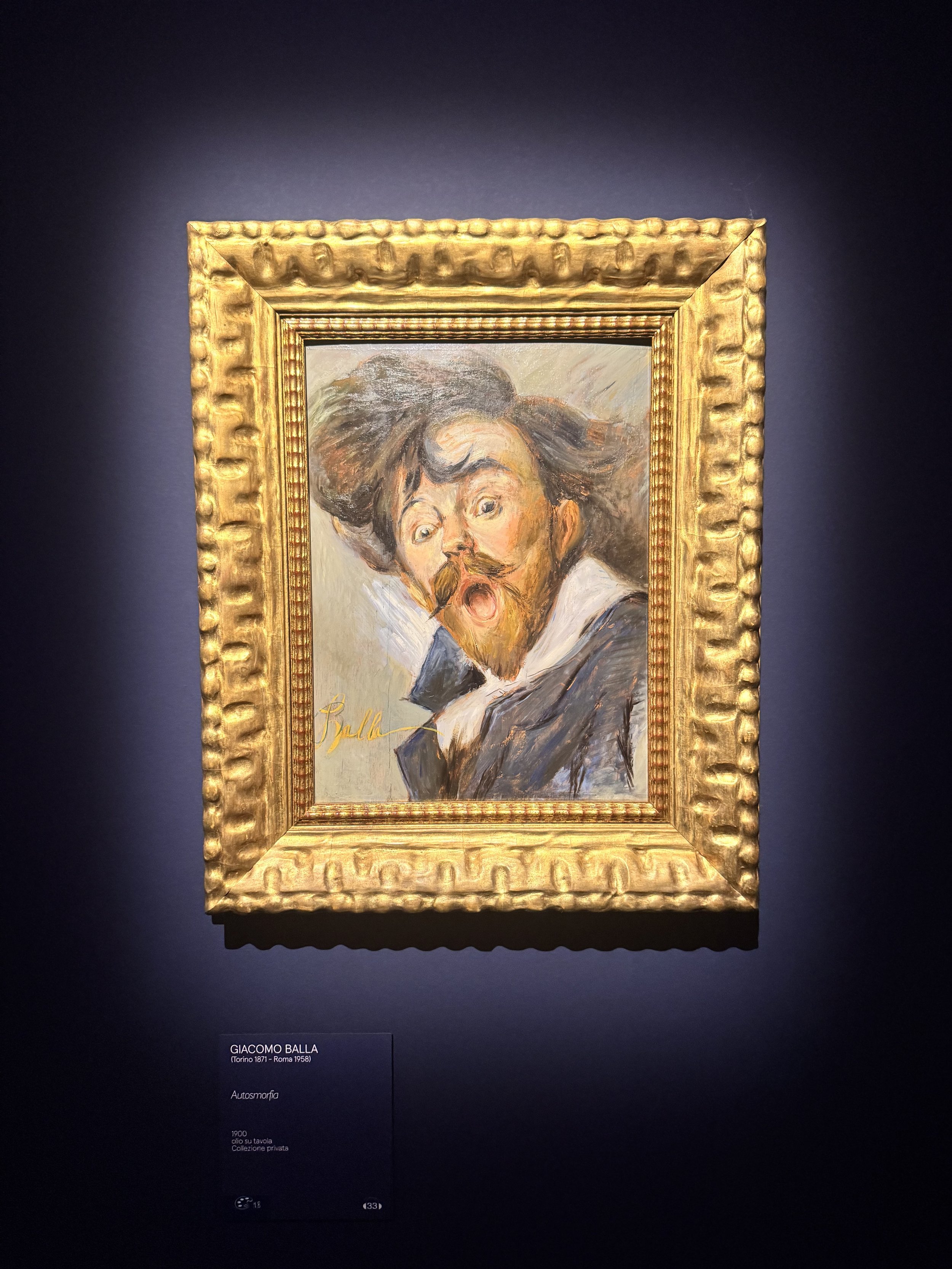

Giacomo Balla, Autosmorfia

In 1900, Giacomo Balla in Autosmorfia (Self-Portrait) painted his self-portrait. It is a colourful, lively artwork; futuristic in its comical jolt. With an expression of feigned great surprise, he is observing something on his side. Yellow predominates: in the frame, in the pigmentation of his face and beard, and in his signature at the bottom. His hair is long and wavy, almost as if it were swinging to the right. His thick eyebrows join two locks of falling hair. A sharply pointed goatee, with a drooping moustache, surround a small, open mouth, forming a precise circle. His movement is decisive, even rapid, involving every part of his face. He is a person eager not to escape the upheavals of the early twentieth century.

Otto Rank, The Incest Theme in Literature and Legend: Fundamentals of a Psychology of Literary Creation, author’s translation from Italian edition Il tema dell'incesto. Fondamenti psicologici della creazione poetica (Sugarco Edizioni, Varese, September 1989)

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book III, lines 407–408, English version (“A. S. Kline’s version”, as indicated on the website) available online at: https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book III, lines 416–418, English version (“A. S. Kline’s version”, as indicated on the website) available online at: https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book X, lines 255–259, English version (“A. S. Kline’s version”, as indicated on the website) available online at: https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm

Sigmund Freud, The Moses of Michelangelo, author’s translation from Italian edition Il Mosè di Michelangelo (Biblioteca Bollati Boringhieri, Turin, first edition 1976, reprint April 2004)

Lauretta Colonnelli, "Alla ricerca della propria immagine," Artedossier, no. 431, May 2025, p. 59. Author’s translation

Press kit: "Il Ritratto dell’Artista. Nello specchio di Narciso" available in Italian online at: https://media.mostremuseisandomenico.it/fondazionegmf/uploads/2025/02/RITRATTO_Cartella-Stampa-completa.pdf. Author’s translation

Aristotle, Poetics, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, The revised Oxford Translation. Edited by Jonathan Barnes, Princeton University Press, N.J., Vol. II, available online at: https://homepages.hass.rpi.edu/ruiz/AdvancedIntegratedArts/ReadingsAIA/Aristotle%20Poetics.pdf

Is narcissism a primary quality for an artist?

Without narcissism, could an artist experience aesthetic and poetic stimuli?

According to the elegant exhibition The Portrait of the Artist. In the Mirror of Narcissus. The Face, the Mask, the Selfie - curated by Cristina Acidini, Fernando Mazzocca, Francesco Parisi, and Paola Refice at the Museo Civico San Domenico in Forlì - the answer is definitive: narcissism is an undeniably and irrefutably inspiring genius.