Living Directed by Oliver Hermanus

Living

Directed by Oliver Hermanus

Starring: Bill Nighy, Alex Sharp, Adrian Rawlins, Hubert Burton, Oliver Chris, Michael Cochrane, Anant Varman, Aimee Lou Wood, Zoe Boyle, Lia Williams, Jessica Flood, Jamie Wilkes, Richard Cunningham, John Mackay, Ffion Jolly, Celeste Dodwell, Jonathan Keeble, Patsy Ferran, Barney Fishwick, Eunice Roberts, Mark James, Tom Burke, Nichola McAuliffe

Countries: UK, Japan, Sweden

Year: 2022

Author: Roberto Matteucci

Click Here for Italian Version

“Infatued?”

In 1951, Akira Kurosawa portrays the complex human difficulties of post-war Japan. The Japanese were defeated and found themselves depressed and vulnerable, forced to confront a convoluted physical and psychological reconstruction. The protagonist of the film Ikiru, Kanji Watanabe, is a bureaucrat, a pen-pusher swamped by paperwork. He reads the paper files meticulously, slowly, and finally, bored, places his seal on the document. His subordinates dubbed Watanabe “mummy”.

What is the difference between a mummy and a zombie?

A mummy and a zombie are both dead. However, the mummy is immobile and bandaged, while the zombie walks, and can kill.

This is the metaphorical difference between the masterpiece Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru and the remake Living, directed by South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus, presented at the 79th Venice Film Festival.

Oliver Hermanus was born in Cape Town. He set two of his films in South Africa: The Endless River and Moffie, which were screened at the 72nd and 76th Venice Film Festivals, respectively.

The Endless River (1) is a brutal story. It is situated in a South African village enveloped by lush nature. The scenic beauty of the country contrasts with the ruthless violence of the small community. An allegory of the nation: wonder and wickedness have coexisted for years.

Moffie (2) is a more elaborate film. It recounts the war between South Africa and Angola. The point of view is from inside a barracks near the front. It is a place exclusively for Caucasian soldiers. A sexual relationship between two conscripts upsets this masculine territory.

The director's thesis is that whites were enemies of blacks, but there were also whites who were marginalised: homosexuals. The author combines and compares the discrimination against blacks and that of white gays.

They are two films with convoluted, difficult reasoning, but with formal, logical direction and clear arguments. The atmosphere of the period is spot-on, including the sociological analysis. In Living, the script relocates the setting to another city. The poignant Kanji Watanabe lives in Tokyo, while William lives in London. The historical period remains the 1950s.

“All the filmmakers I spoke to [beforehand] when I was saying, “Oh, I’m really thinking of doing this movie in England,” I’d always wait a minute to say, “It’s a remake of a Kurosawa.” (3)

The plot scrupulously follows the original. William is a senior member of the London County Council. His job wouldn't be boring, but years of repetitiveness and deprivation of any involvement have made it gloomy and tedious. When the doctor diagnoses him with only a few months remaining due to stomach cancer, he faces an existential question: what has he done that is important in his life?

He has a grown-up son who is married. He raised him alone; his wife had died. His son is distant and interested solely in his father's money. Distraught, William skips work for the first time in his life, eliciting astonishment from his subordinates. He meets new friends, gets dragged to encounter women in karaoke bars and clubs. He meets Miss Harris, a delightful former colleague.

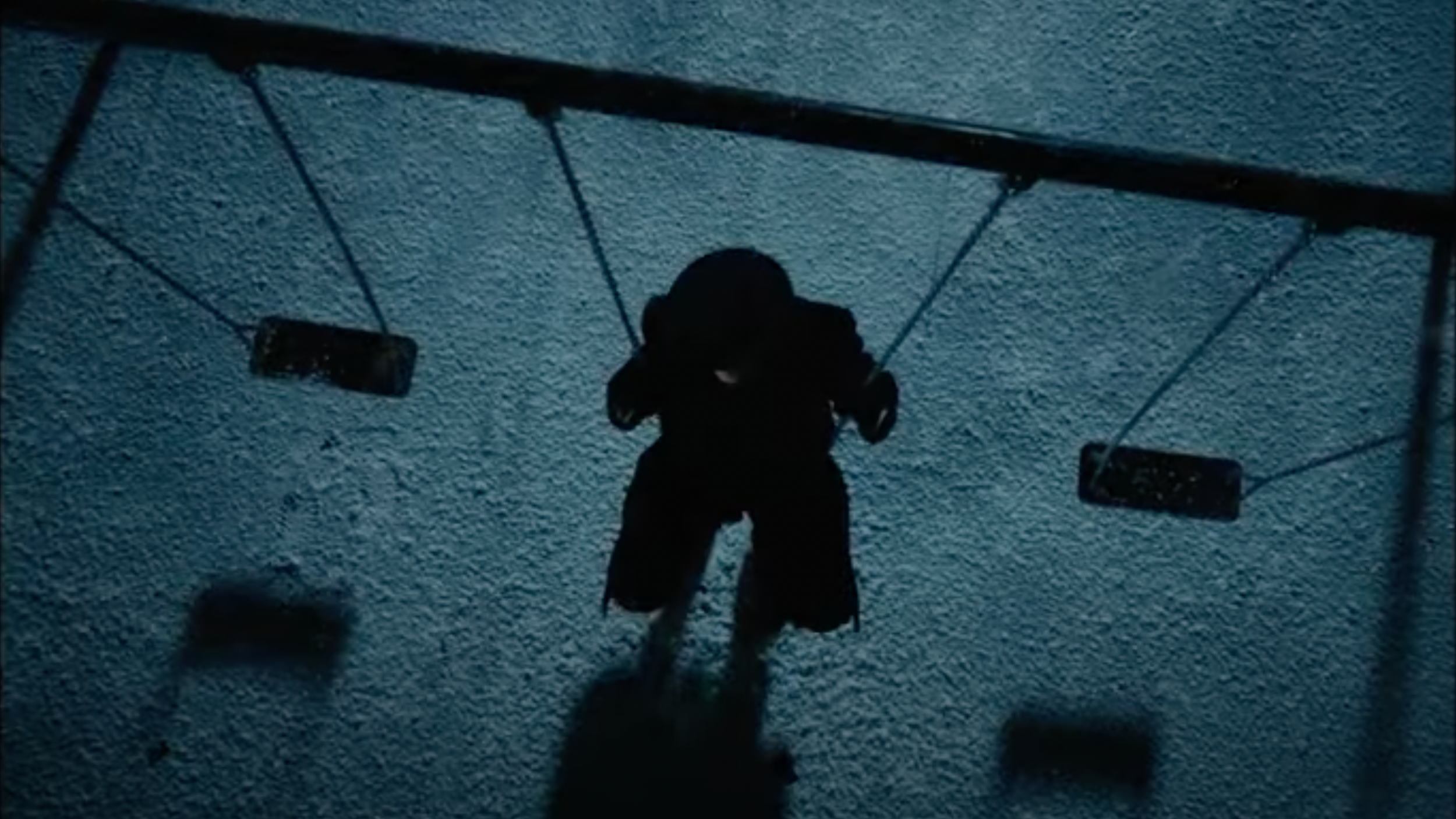

Their friendship develops and becomes close. William tells her about his disease. Now he is freer and craves a challenge, a victory to motivate his existence. He returns to the office and seizes a random dossier. The file is a petition from a group of mothers. They submit that the council clean up a patch of land hit by a bomb in World War II. In its place, they would like to have a children's playground. A worthy request, but not essential. William is not invested in the goal; he does not want to change the world, but he seeks a personal triumph over bureaucracy. It is not easy. Here, he is on the other side. He must convince many reluctant municipal managers and employees, like he once was. Patience, meticulousness, and tenacity allow him to face his first and last undertaking; indeed the children will have their own swing.

An absurd task for the South African director: directing a reimagining of a masterpiece by Akira Kurosawa, rightly considered a genius. What other director would have risked it?

Oliver Hermanus explains in an interview:

“... “It’s a remake of a Kurosawa.” And that’s when all of the friends would start screaming and running around going, “Are you nuts?” So it had that effect in my life for a while. [laughs]” (4)

His friends have an honest reaction: “Are you nuts?” They are right. Anyone would have declined; the risk of being a loser is enormous.

Oliver Hermanus obviously did not outdo Akira Kurosawa, but he held his own.

The producers asked to shift the perspective; William is English and must live in London:

“Q: Right from the beginning, there’s a technicolor-looking image of 1950s people walking down the street, and a key character, Peter Wakeling [Alex Sharp], is waiting in the train station. It really sets the mood for this scene of manners on the train in the 1950s. You are originally from Cape Town, South Africa, and you made a transition yourself to a very different setting. How was so it carefully crafted? OH: I was looking at references to old imagery and was watching a lot of films [from that era]. I wanted London to be quite cinematic, so that meant that I was playing a lot with tropes that I’d seen in old movies that I really liked, and had developed ideas that I had from photography — approaching England really as an outsider and really wanting to make it my own. The reason why the producers also wanted me to do this film was because I wasn’t from the UK and that I would, somehow, bring a different eye to it. There was the invitation to do that, so I was very willing to pick and choose how I wanted to frame England.” (5)

Oliver Hermanus succeeds in describing a vibrant and technicolour London. William is perfectly Anglo-Saxon. Indeed, the author uses a classical topos, such as double-decker buses and train journeys, to create a recognisably British ambience. The director confirms: “I was playing a lot with tropes.”

The psychology of life has an equal thematic astuteness. The author speaks of hope and the search for a fulfilling life:

OH: “The hope is that the focus and echo of the original is the same message, which is, to be present in your life and find a center that allows you to operate and be part of the world in a fulfilling way — not so much in the sense of grandeur and as a monument to oneself, but in the sense of knowing that on any given day the life that you live, the time you spend, is coming from a place inside of you that’s truthful, connected and self-aware. This movie has a small message but an important one.” (6)

Why does one live? What is life's purpose? Did William help people in his long career as an employee? What would have been the meaning of his profession and his dedication to the bureaucracy for which he lived? The playground is a contingent choice. Surely, in every department, there is an appeal that contains a need for solidarity, perhaps insignificant. Yet such a request should not be set aside, but resolved.

It is the struggle for a comprehensive and fair public administration. There is a precise and solvable rule; bureaucracy must not be a machine of “no,” but must find equitable solutions.

Located in the same era, another satirical Cuban film on the same subject: Death of a Bureaucrat (in original La Muerte de un burócrata), by director Tomás Gutiérrez Alea. (7) In La Muerte de un burócrata, the battle against the evil of bureaucracy is merciless, even joking with death.

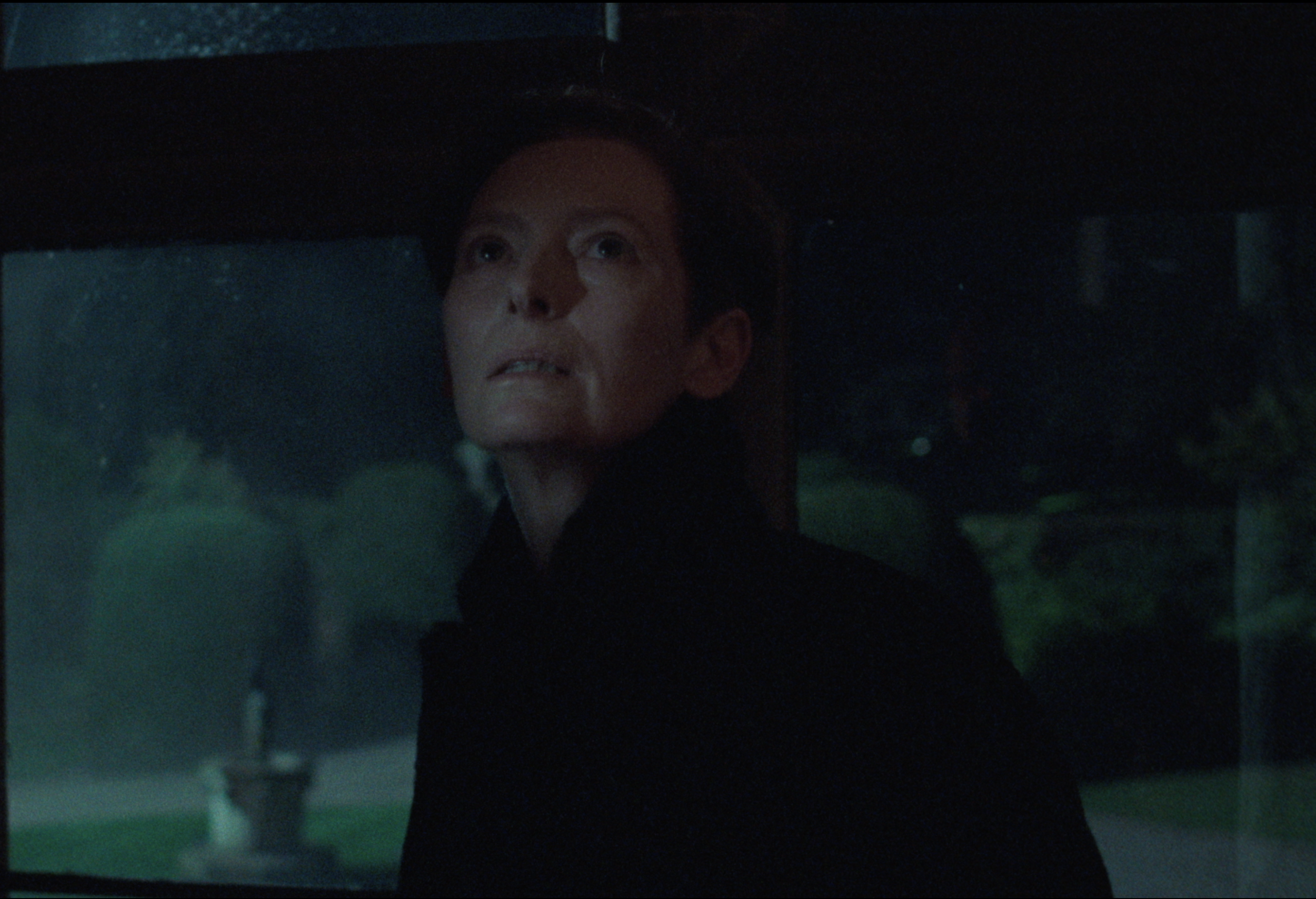

William is sad, melancholic, fragile, and tormented. He is indolent and lethargic at work. It is his old habit; his illness has nothing to do with it. His sullen attitude is caused by loneliness.

William's characteristic scenes are many.

The son is dominated by his selfish wife and intimidated by his father. The son avoids speaking, caught between his father’s expectations and his wife’s demands. William's life is meaningless. Everything changes when he sets out resolutely to settle the playground dispute. He walks with determination, single-file with the other employees.

Or, he is mysterious in his bar hopping in London's many bars and clubs at night.

Or, in a karaoke, anguished, he sings the heartbreaking song The Rowan Tree.

Or, when he sleeps on a girl's shoulder at a cabaret show.

He seems like a stalker with Miss Harris. Nevertheless, he does not hide any ulterior motive; William is a simple person. With kindness, he enters the woman's soul, until they become friends. Miss Harris and William confide in each other. William reveals his illness while Miss Harris reveals William's nickname. In the office, colleagues called him: Mister Zombie.

However, William maintains a regal dignity even when hiding the blood-stained handkerchief. After all, as a child, he dreamed of being a gentleman: “... what I wanted was to be a gentleman.”

The film is compelling, well-structured, with a persuasive character presentation, a dual conflict: the intimate one of a man aware of his impending death versus his bureaucratic existence. Bureaucracy is cruel, sadistic, inhuman, criminal whether in Japan, England, or Cuba. An unequal conflict. Death and bureaucracy will unceasingly be the final victors, yet they can be annihilated in courageous battles if fought vigorously. Therefore, William begins to fight, wanting to cling to life.

The narrative has rhythm. William moves restlessly, alternating presence and absence.

Home sequence. Fade. It is an oppressive house. William is sitting in the dark. He listens to his son and his daughter-in-law. They are returning home and talking about asking him for the severance pay. William is totally obscured, but he is still present.

Or, the dinner scene. The son's silence and the clatter of dishes create an awkward, muted tension. The ellipsis occurs with the shot of the calendar.

The same happens at work. When he is absent from the council, the camera films his empty usual seat. His peers around the bench desk gossip about the reasons for his absence, his replacement, and the need to report him missing. William is physically removed, but at the same time, he is present.

Or, William is shot in a high-angle shot with his head down, ashamed, thoughtful. William is visible but unfairly oppressed.

Or, the office scene with the heads out of frame.

Or, when the director focuses on William's face while in other shots it is blurred, indeterminate. William is both absent and present.

These are examples of William-centric rhythm. This feature of the film decides the structure of the narrative.

The tension is mild, soft; there are no dramatic gestures, but a constant, steady pace. The director emphasises this in his tilt-shot , in the overtly fake backdrops, and in the opening aerial-shot Many people are walking quickly, the loud clacking of heels. At the station, a new recruit on his first day joins his future cohort. The welcome is detached; everyone minds their own business. They take the train together. It is a longstanding habit, and they go through the motions. Their boss also gets on, but sits in a different carriage. Only upon arrival, they greet each other and proceed collectively, but in silence. Shot-reverse shot and rear-view shots are the technical specifications.

This interpretation does not allow sudden shifts, but unfolds a flowing tale, a natural condition abundant in ethical elements.

There are social ones too. Can an English gentleman be compared to a Japanese who has survived the war? This is the real dissimilarity between Kurosawa and Oliver Hermanus. Kanji Watanabe is the loser, William is the winner. Kanji Watanabe represents drama. He is the symbol of a depressed, disastrous Japan, whose values are in deep crisis. Leonardo Vittorio Arena addresses this situation in Lo spirito del Giappone. La filosofia del Sol Levante dalle origini ai giorni nostri (BUR Saggi Rizzoli, Milan, 2008, p. 366):

“After the end of World War II, the Japanese lost self-confidence calling into question their ancient scale values. They were victims of a sort of alienation: they could no longer find comfort in the old world, nor did they understand how to make room for themselves in the new one. To break the impasse in response to which many chose suicide or isolation, nothing is more effective than invoking a supposed sense of superiority rooted in an ancient tradition. The dramatic condition of the Japanese in the postwar period has been shown in films such as Kurosawa's Ikiru...” (8)

Kanji Watanabe, Ikiru (1952), Akira Kurosawa

Kanji Watanabe is pedantic, monotonous, shy, weak, polite, modest, with a downcast gaze. His close-ups are intense, those eyes lowered toward his feet before everyone, his tear-filled eyes express his pain. The audience fully identifies with Kanji Watanabe, an identification transformed into love for his bashful eyes. Kurosawa creates Watanabe's character, constructing a black-and-white reality, in contrast to Oliver Hermanus's sophisticated colour. William is not a loser; he won the war. The empire is disappearing, but William still wants to be a gentleman.

Another crucial divergence. Oliver Hermanus outlines an introspective plot; for the author, it is a personal, private matter; no social goal, but exclusively an individualism rich in humanity, yet deliberately unemotional.

Kanji Watanabe's eyes are Japan, and Japan is:

"... special, favoured by the kami, hard to fall." (3)

Kanji Watanabe reacts with courage, not only for himself, but extending his action to his entire office, restoring integrity to bureaucracy.

The Mummy defeats the Zombie: Kanji Watanabe's tearful eyes remain in the heart.

Roberto Matteucci, “The Endless River”, September 23, 2020,http://www.cinemah.com/neardark/index.php3?idtit=1774 (accessed 4 February 2026)

Roberto Matteucci, “Moffie Directed by Oliver Hermanus”, July 10, 2020,https://popcinema.org/film/moffie-regista-oliver-hermanus (accessed 4 February 2026)

Stephen Saito, “Kazuo Ishiguro and Oliver Hermanus on Making the Most of Living”, December 23, 2022, https://moveablefest.com/kazuo-ishiguro-oliver-hermanus-living/(accessed 3 February 2026)

Stephen Saito, “Kazuo Ishiguro and Oliver Hermanus on Making the Most of Living”, December 23, 2022, https://moveablefest.com/kazuo-ishiguro-oliver-hermanus-living/(accessed 3 February 2026)

Nobuhiro Hosoki, ”Living : Exclusive Interview with Director Oliver Hermanus”, December 24, 2022, (*) https://cinemadailyus.com/interviews/living-exclusive-interview-with-director-oliver-hermanus/ (accessed 3 February 2026)

Nobuhiro Hosoki, ”Living : Exclusive Interview with Director Oliver Hermanus”, December 24, 2022, (*) https://cinemadailyus.com/interviews/living-exclusive-interview-with-director-oliver-hermanus/ (accessed 3 February 2026)

Roberto Matteucci, “La muerte de un burócrata - The death of a bureaucrat Director: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea”, June 12, 2020, https://popcinema.org/movie/la-muerte-de-un-burocrate-directed-tomas-gutierrez-alea (accessed 4 February 2026)

Author’s translation from the Italian edition: Leonardo Vittorio Arena, Lo spirito del Giappone. La filosofia del Sol Levante dalle origini ai giorni nostri, BUR Saggi Rizzoli, Milan, First Edition, January 2008

A metaphorical comparison between Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru and its remake Living by Oliver Hermanus, presented at the 79th Venice Film Festival.